Archive for the ‘SOA’ Category

SOA, BI, and Knowing Your Customer

SOA, BI, and Knowing Your Customer

Strategy is an interesting beast. It typically begins at such a high level that it’s possible to make connections between virtually any goal and any effort of a strategic nature, like SOA. At the same time, simple connections between those goals and efforts can be of, well, strategic importance. For this entry, I wanted to take one of those typical goals and try to bring it into the world of SOA and make some of those connections. Some of you may read this and just go, “Well duh, that’s common sense” while others may find something of significant value. I’d really like to hear your feedback on this entry. Strategy is one of those areas where people would many people in the trenches want to contribute, yet ultimately feel disconnected from it or that it doesn’t impact them. At the other end of things, the strategy makers want things to ripple down the trenches and for individuals to know that they are contributing to strategic success, yet their work is easily dismissed as being “fluff” or “ivory tower.”

The topic for today is knowing your customer. There’s no doubt that many, many companies likely have some strategic goal that can be tied back to customer support. The March 2007 issue of Business 2.0 had an article on “The Quest for the Perfect Online Ad” and it all comes down to better targeted advertising, which in turn, means knowing your customers. I would venture to guess that most companies try to do this through some form of data warehouse and business intelligence system. So how does SOA come into the mix? There’s actually two ways that I envision it having a role. First, it can enable a greater level of visibility into customer actions, presuming there’s some system interaction associated with the customer’s actions (sorry brick and mortar guys, not much SOA can do). Let’s presume that the system they use is a monolithic application. Your only source of input are the boundaries of the solution. If it’s a web application, you’ll have a clickstream, which can be pretty good, as evidenced by the levels of personalization from Amazon.com. If it’s a thick app, you may be limited to just extracting information from your transactional store, representing only the end outcome of the user’s efforts.

SOA, if done properly, should make it much easier to capture the user’s actions for later analysis. You’ll break down that monolithic application into a collection of services. These services represent boundaries within the solution, and at those boundary points you can leverage standardized infrastructure to log incoming requests and outgoing responses. This is even better than a web clickstream, because there you have to recreate the web page and understand what data elements were shown to the user on the page. If you’ve got the service request and response that returned the raw data tagged with the customer identifier, you’ve saved yourself a bunch of work associated with removing the presentation components. By pulling those messages into your BI system and analyzing the content of the message, you should begin to gain more knowledge about your customers.

The second way that SOA should come into play is in providing access to the data warehouse and business intelligence system to personalize the user experience. Rather than strictly being a source of reporting information for some person to look at, the information gleaned from those systems can be made available as services and factored back into the interface presented to the customer.

You may read this and think this is all common sense, and I actually hope that’s the case. Sometimes, however, we’re so buried in the technology or tactical issues that we fail to take the time to think strategically. It would be very easy to build the application in a service oriented manner and never bother to make use of the fact that this content is available and could provide valuable information for improving the customer experience. This is part of thinking outside of the box and beyond the functionality at hand. Hopefully reading this entry, whether you think it is common sense or not, will help you do that!

Widgets, Gadgets, Mashups, and Composite Applications

Widgets, Gadgets, Mashups, and Composite Applications

In the recently released SOA Insights Podcast, Dana and guests discussed the wacky world of mashups and composite applications. The panelists all agreed that mashups and composite applications are effectively the same thing, however, they did state that mashups tend to be associated with web-based presentation more so than composite applications. The debate moved into a discussion of SaaS providers (e.g. Salesforce.com) and aggregators like StrikeIron. Google apps was also thrown into the mix, however, I don’t consider that a mashup or a composite application. Google Calendar or Google Spreadsheet are really just hosted versions of traditional desktop applications. Given that the conversation went this direction, it surprised me that the discussion did not go down into the area of Widgets and Gadgets, depending on which operating system you like.

Before we go there, let’s first look features of mashups. The most familiar notion of a mashup is a geographic overlay of some information on a Google map. This is possible through the availability of data as XML from simple HTTP calls, the scriptability of a web-based presentation component, such as Google maps, and the use of AJAX technologies to tie the two together. How does this relate to SOA? The most direct connection is in the first item: data services making data available as XML over HTTP. Without this, everything needs to move to the server side where data access frameworks like ADO.NET, Hibernate, etc. can be leveraged. The other half of this is the presentation tier, where the combination of JavaScript and CSS now allows HTML-based components to effectively expose an API that can be executed within a browser. This is in contrast to Portal technology, which is still a predominantly server-side technology. Effectively, JavaScript and CSS now allow a component-based model for web-based application development.

To make this more applicable in the corporate world, we need to look at the corporate problems. Many enterprise IT department are not creating applications for an end user on the internet, but rather for their own corporate employees. Frequently, these applications are used for simple tasks (think data entry) associated with the execution of a business process. Unfortunately, those applications take time to run. If they’re desktop applications, there’s probably a lot of bloat in them and they take a lot of time to startup. On the consumer side of things, I’ll use Quicken as an example. I may only need to enter one or two transactions, but I used to have to start the whole bloated application with all of its features to do so. Something that should take 30 seconds winds up taking 2-3 minutes.

Now, let’s enter the world of Widgets and Gadgets. It really started with a program called Konfabulator (which was eventually acquired by Yahoo), continued with Apple’s Dashboard, and most recently was continued with Microsoft Vista’s dashboard. Effectively, these platforms leverage DHTML, JavaScript, CSS, and if necessary, some platform specific APIs (mainly for saving preferences, but can be used to access local desktop resources), to present web-based applications that are very narrow in function. For example, the latest release of Quicken for the Mac included a Dashboard Widget that allows data entry. I no longer have to start all of Quicken simply to enter a transaction. This results in increased efficiencies. Because these Widgets and Gadgets are built using DHTML, JavaScript, and CSS, they can pull in data on the fly via XML over HTTP, instead of having the user navigate through endless pages to get to what they need to do. Furthermore, the platform integration allows data to be carried in to the widget and be “mashed” on the fly.

I believe these technologies have the most potential within the enterprise. I can’t drag an Word document into a browser window normally, but I can drag it onto on Apple Dashboard Widget (I don’t know about Vista Gadgets). Secondly, their lightweight nature and immediate access makes them extremely well-suited for workflow tasks. Theoretically, the widget itself could be embedded in a task notification message. The task manager for the user (which could be a widget/gadget as well, or it could be something like Outlook) would leverage the native HTML/CSS/JavaScript engine to generate the UI on the fly, pull in the data via XML/HTTP and allow the user to directly execute the task without all of the overhead of launching applications and navigating through web pages.

There are certainly still challenges that exist before this becomes mainstream, security being the largest, along with the risk of badly coded widgets consuming resources. If you’ve ever tried to do some AJAX programming and used timers, you’ll know that it’s easy to make a mistake and wind up with a ton of background HTTP calls trying to get XML data that just grinds the system to a halt. This is just the normal maturity curve for technology usage, however. As someone with interest in user productivity and efficiency, I’m excited about the opportunities that Widgets and Gadgets may provide for all of us, both corporate user and home user, in the future.

Consumer-Oriented *

Consumer-Oriented *

Brenda Michelson just posted a blog entry titled How do you “Talk to Everyone”? She’s working on a whitepaper based upon the SOA Consortium‘s Executive Summits, and had recently read Jon Udell’s post on “Talking to Everyone.” She shared the following excerpt from her work-in-progress:

“To collaborate effectively, business and IT professionals must speak a common language. Historically, business professionals have been encouraged to increase their IT literacy. This has proven successful at the project execution level. However, collaboration on strategy and architecture is a business conversation first.

“Our entry is always the process and that’s what we actually talk about – how to optimize the process, how to drive the process…When I hear business people talk about systems and they mention System A, System B, System C, I know we’re in trouble. Because basically that means to me is that we are locked into the constraints of the environment.� – CTO during SOA Executive Summit

The CIO and CTO participants encourage business-smarts in their IT organizations. IT professionals, particularly senior leaders and enterprise architects, must understand the business, and be able to relate IT capability to business value generation.”

This brought me back to the first public presentation I gave on SOA. After presenting, one of the questions asked was, “How do you talk to the business about SOA?” My answer was that I don’t talk about SOA, I talk about the business. The business discussion should create the context for a discussion about SOA, not vice versa.

The real point of this message, however, is the notion of consumer-oriented actions. Any public speaker will tell you that’s it’s important to know your audience. While I’ve never stopped and asked my audience some background questions as some presenters do, I’m sure that there are presenters who use this practice and actually do adjust their communications on the fly based on the results. Likewise, if I’m building a user interface, it’s important to know characteristics of the end user. It’s typically even better to have a real end user involved, rather than make assumptions. The same thing applies to service development. A service, first and foremost, needs to do what its consumers want it to do. Furthermore, the more it presents itself in a manner that the consumer understands, the more likely they’ll use it.

In general, I believe that any activity will have a greater chance for success if it is focused on consumption first. Unfortunately, this is seldom the path of least resistance. The past of least resistance is to put things in a manner that you, the provider, understand well. Guess what, not everyone thinks like you. It’s even likely that the majority of people don’t think like you. To be successful, you need to understand that world of your consumers. Don’t go and talk to the CEO if you don’t understand the things that he or she thinks about on a daily basis and finds important. Do your background, and position yourself for success by learning the environment of your consumers and doing your best to make it the path of least resistance for them, rather than the path of least resistance for you.

Moving from a project-based culture to a product-based culture

Moving from a project-based culture to a product-based culture

Many people have frequently stated that the biggest challenge in adoption SOA is the cultural change. That’s an easy statement to make, but how do we qualify what we mean by cultural change? Merriam-Webster provides this definition of culture:

The set of shared attitudes, values, goals, and practices that characterizes an institution or organization

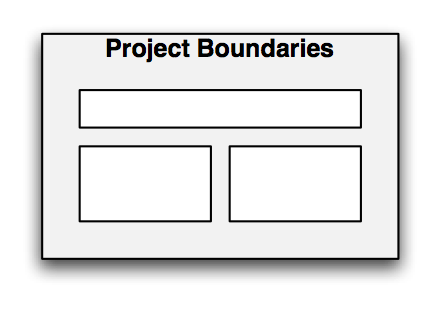

One of the attitudes and practices that arguably most organizations practice is that of the IT project. Things in IT get done by creating a project. An idea is generated by someone in the organization, typically the business side, a project is defined and funded, IT provides the solution, and the team goes on to the next project. So why is this a problem? Without projects, how would work get done? The problem that this culture creates is the dimensions of the project control all decisions. Here’s a picture that illustrates this.

Projects are wired to create things like this:

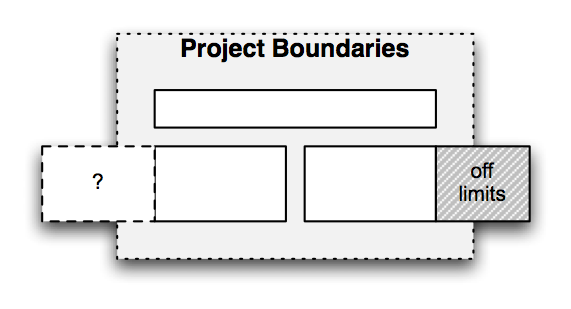

The problem is the project boundary is not a system boundary. It’s an artificial boundary. The components that comprise the project solution represent the real boundaries, but because of the project constraints, they’re unable to to set those boundaries correctly, either because they were constrained from performing appropriate analysis to figure out what they should be, or they were told that funding didn’t allow the “right” thing to be created. It looks like this:

When those project boundaries become system boundaries, the result is the monolithic application, which I think we’d all agree is a bad thing. Even where the appropriate boundaries were determined, the project-based organization will likely struggle to match a team to that subcomponent for proper lifecycle management. While many organizations certainly have teams that continue to provide subsequent releases for a solution, those releases are still defined along those original project boundaries, not the correct system boundaries. Coupled with that, project-based organizations think in terms of linear, project lifecycles:

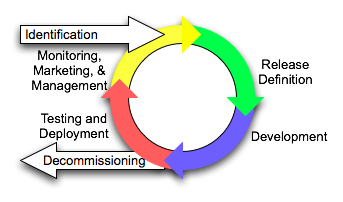

Where organizations need to go is to adopt a product-based culture based upon appropriate system boundaries, not on project boundaries. A product-based culture presumes a lifecycle like this:

Projects should be created to manage the efforts associated with a release of a product, but projects should not be the source of our system boundaries. In addition, the product-based lifecycle has that final activity of monitoring, marketing, and management, the three M’s. All too often, the project-based organization just throws things over the wall when their linear lifecycle is complete, and the only thing that happens is some alert-based monitor to notify someone when something breaks. This step needs to be formalized so that proactive monitoring takes place to increase understanding of how the service is used, including trend analysis to understand why it behaves differently (even if nothing breaks) under certain conditions. The service needs to be marketed to the community to identify new consumers and new requirements. Anyone who’s tried to achieve reuse of software within an enterprise will tell you that successful marketing is critical to this effort. Finally, all aspects of the service must be managed. This means communicating with existing consumers, updating contracts and policies as needed, sharing usage information, and doing everything possible to demonstrate that you have control over everything about this service.

This approach certainly has its challenges. From an organizational perspective, you can’t simply map a team to a given service, because the release cycle for a product may be so long that it can’t keep a team 100% occupied. A better approach is to align organizational teams around service domains, so that the team manages enough services to keep them occupied, but similar enough to allow depth of knowledge in a given area. These could be horizontal domains, focused on infrastructure libraries, or they could be vertical domains, focused on areas of business capability. Odds are your organization will require both, just as it likely has separate teams today that specialize in technical infrastructure typically purchased from a vendor from groups that specialize in more vertical application development.

If SOA could be done as a project, these organizations would be doing it. The problem is that it can’t. Many organizations are tying SOA to some major initiative which has significant breadth of scope such that the right boundaries for services can be determined, however, if they don’t find a way to transition to a more product-like development model rather than a project-like development model, they’ll still struggle after that initiative is complete.

Challenge of Centralized Service Teams

Challenge of Centralized Service Teams

Vilas recently posted on centralized service delivery teams (SDTs), and invited others to share their experiences. I haven’t posted on this subject in some time, and as I thought about it, I realized that my opinions have evolved.

Why would an organization consider a centralized team? Frankly, I think it comes down to governance. It’s far easier to achieve consistency within a single group than it is across many groups. But what are the downsides to this approach? Probably the biggest one, and the one of most concern when adopting SOA, is the that of business domain knowledge. While it’s probably relatively easy to pick and choose from among the development staff to get a set of people with broad technical knowledge, it will probably be more difficult to find people with broad business knowledge. What will be more important to your SOA efforts? Technical consistency (i.e. all services are Web Services) or business consistency? The answer will probably vary based on whether you see SOA as primarily as a technology integration solution, or if you see SOA as a business agility solution.

Personally, if I had to pick one over the other, I’m more interested in the business agility aspects. I hope I don’t have to pick one, however, because the technology integration aspects are not something to be dismissed. What does that mean? It means I’d take the key experts on the business domain for a service rather than having the technical experts. Given this preference, it certainly means that a staff augmentation model for service development may make the most sense, rather than an outsourcing model. In this approach, we’d have a pool of technical experts that would be allocated to service development efforts, with the work managed by those projects, rather than by a manager of the pool. In this way, service ownership can be established from the beginning, and that owner will be the person who understands the business domain and the needs of the consumers of that domain. This is very important, as we need to shift the organization from being concerned about development lifecycles (end with the project) to service lifecycles (end when service is decommissioned). An outsourcing model of development is focused on the development lifecycle only, and can easily result in services going into limbo after the initial development effort.

Now there is one caveat to this. Organizations that may be considering a centralized service development team may not have any understanding at all of service ownership. It’s likely that the project that needs the service is building the service consumer. Assigning a resource to this project to perform service development does not do what I’ve described, because the project is not the service owner. The project manager is not the service manager. Who is it, then? Well, that has to be determined, and if the organization doesn’t have any teams that are prepared to act in this capacity, they’ll need to create one. It’s important to define this team according to business domains not technology domains, presuming we’re talking about business services and not technology services (like Security Services). This is where the needs may challenge the current organizational structure. New teams will likely need to be formed. Are these “centralized” teams? These teams may wind up living in the organization for a long time, unlike a Competency Center or Center of Excellence type approach. If anything, the Center of Excellence may be the group that is the one making these organizational and ownership decisions and thus beginning the organizational transformation that will occur. The COE may not be the group building the services, but they may be the group with the appropriate breadth of experience and knowledge to make the necessary decisions to set the organization in the right direction for the future. If there are five teams that all conceivably be the service owner, which one do you pick?

As these decisions are made, the center of excellence will disappear, but the new service development organization will now be in place, where there are groups dedicated to service creation as well as groups dedicated to the creation of user-facing systems. How many organizations that have “adopted SOA” have reached this point of maturity in their efforts?

Automate what part of SOA Governance

Automate what part of SOA Governance

I must be in a bad mood this week (which is unusual for me, I consider myself an optimist), as this will be my second post that could be considered a rant. I just read David Kelly’s article on eBizQ, “Improving Processes With Automated SOA Governance.” For whatever reason, that title alone struck a nerve. Clearly, the whole topic of automation points to tooling, which points to vendors. Once again, this is putting the cart before the horse.

The primary area for automation in SOA Governance is policy enforcement. Governance isn’t just about enforcement, however. Governance is about people, policies, and process. People (the legislators) set policy. Policy is enforced through process. That may be a gross oversimplification, but it’s the way it needs to work. Often times, enforcement fails because the people, the policies, or both are not recognized. Even if you automate enforcement, if the policies and the authority of the people setting the policies aren’t recognized, your governance efforts are less likely to be successful.

Let’s use the common metaphor of city government. Suppose the new mayor and the city council want to cut down on the number of serious accidents involving cars and pedestrians that have been occurring. Clearly, we have people involved: the mayor and the city council. The city council proposes a new policy, and in this case, it’s lowering the speed limit on side streets from 30 mph to 20 mph. The mayor approves it and it becomes law. If the town has a problem with speeders, and they don’t recognize the authority of the city council to establish speed limits, they’re probably not going to slow down. Enforcement takes three forms: posted signs, police patrols, and a few of those “How fast you’re going” machines that have an embedded radar gun and a camera. Posted signs are the most passive form of enforcement, and the least likely to make a difference. Police patrols are the most active form of enforcement, but come at a significant cost. The radar gun/camera system may be less costly, but is not as active of an enforcement mechanism. A ticket may show in the mail. Clearly, the best way to do enforce it would be to wire in some radio transmitter into the street signs that communicates with cars and doesn’t allow them to go over the speed limit in the first place, but that’s a bit too intrusive and could have complications. Of the three enforcement solutions, none of them address the problem of someone who does not recognize the authority of the people and the validity of the policies. This is a cultural issue. Tools can make non-compliance more painful, but they can’t change the culture. If you’re having problems with your governance, I’d look at your people and policies first. If you’ve got recognition on the authorities and the policies, now you can look into minimizing the cost of your enforcement through tooling. It is certainly likely that automated tools will be less costly in the long run than having to schedule two hour meetings with your key legislators for every service review.

External consumers and providers

External consumers and providers

James McGovern, in his links entry for April 11th posted this comment in regards to my entry on what SOA adoption actually means:

“A measurement that would be interesting is to ask enterprises how many services do you have that are consumed outside of your enterprise. The numbers would be dramatically lower…”

As I thought about this, it became more and more interesting. First, I definitely agree that the number of services is going to be dramatically lower, unless your company is already a service provider (think ASP), in which case, then it should constitute the majority of your service portfolio. What about other verticals, however? Certainly supply chain interactions will involve external entities. Truth be told, there’s lot of potential for interactions with partner companies. How many companies outsource payroll processing to ADP or someone else? I’d venture a guess that there are probably areas for commodity services in every vertical. Over time, things that once were competitive differentiators become commodities. Once that happens, a marketplace opens up for commodity providers that focus on operational excellence and low cost, and the companies that prefer to focus on customer service get rid of their homegrown infrastructure and leverage the commodity provider. Guess what, when that happens, the potential now exists for service interactions. I recently presented some introductory information on service concepts and described business services as services that both ones that represent the primary business functions as well as ones that support the primary business such as HR, payroll, etc. Technology clearly plays a big role in both.

You may be thinking, “No arguments on what you said, but James asked about services consumed by outsiders, not provided by outsiders.” Quite true, but again, I’d be willing to bet that the vast majority of these B2B interactions will require bi-directional communications. It may be the case that 90% of the time, the partner acts in the service provider role, but odds are that some of that processing will require them having the ability to make service calls back to you. At a minimum, some form of events should be flowing back into your infrastructure. The more information flow can be a circle, rather than a one-way line, the greater the potential for leveraging emerging technologies like CEP for continued innovation. If the information only flows one way, you severely restrict your ability to innovate based on that information.

Aside:James also posted some musings on Open Source and the possibilities of it playing a role in commodity vertical applications yesterday. If that happened, there would certainly have potential implications. It probably wouldn’t take long for someone to create a hosted solution for these open source offerings, again creating the potential for service interactions between the two companies.

The end result of my thinking on this is that if your thinking on SOA is constrained to inside your firewall, it won’t be very long at all before you need to extend that thinking, both as a consumer of services provided from the outside as well as a provider of services that will be consumed by the outside. Companies that make the claim that they’ve “adopted SOA” should have a view that encompasses all of it, regardless of whether their core business is being a service provider or not.

Great discussion on non-functional aspects of SOA

Great discussion on non-functional aspects of SOA

Ron Jacobs had a great discussion with Mark Baciak on ARCast over the course of two podcasts (here and here). In the second one, they discuss Mark’s Alchemy framework. It is essentially an interceptor-based architecture coupled with a centralized store and analytic engine. In my “Converging in the middle” post, I talked about the need for mediation capabilities that address the non-functional aspects of service interactions. Now, most people may see the list and think that an ESB or an XML/Web Service Gateway is the way to go about it. In these podcasts, Mark goes over their system which provides these capabilities, yet through a “smart node” approach. That is, the execution container of both the consumer and the provider is augmented with interceptors that can now act as an intermediary, just as a gateway in the network can.

The smart network versus smart node discussion falls into the category of religious debates. Truth be told, both ways (and the third way, which is a hybrid between the two) can be successful. There is no right or wrong way in the general sense. What you need to do is understand which effort is most likely to produce the operational model you desire. A smart node approach tends to (but doesn’t have to) favor developers. A smart network model tends to (but doesn’t have to) favor operations. As a case in point, I’ve seen a smart network approach that would not be feasible without developer activity for every change, and I’ve seen a smart node approach that was very policy-driven and operations-friendly. So, as an alternate view on the whole problem space, I encourage you to listen to the podcasts.

SOA Adoption – What does it mean?

SOA Adoption – What does it mean?

Evans Data Corporation released another survey that stated that, according to Sys-Con’s article:

…close to a quarter of enterprise-level developers indicated that they already have service-oriented architecture in place, and another 28% plan to do so within the next 24 months.

I have two major issues with this. First, while I don’t mean to diminish the role of the developer, that’s not the person I would be asking about SOA adoption. From a developer’s perspective, this could mean anything from having used web service technologies within a single project to having tens or hundreds of shared services, orchestrated by BPM solutions. What does the Chief Architect or the CIO say? That would increase my faith in this data, although, there’s still problem number two. What does it mean to adopt SOA and how do you know when you’re done? The statement in the Sys-Con release says, “have service-oriented architecture in place.” Again, what does that mean? You don’t put SOA in place, you put services in place. The architecture is the set of guiding principles that led to the particular services that are in production. What is the domain of those guiding principles? Was it at a project level? A line of business? The entire enterprise? I would have liked to see every respondent who said they had SOA in place also answer a question asking them to describe their SOA and then do some analysis on the responses. It certainly could have made for some good quotes.

This does come back to the notion of a maturity model, or at least some form of assessment criteria. In the maturity model that I’ve worked on and continue to refine, the very first level above ad hoc activity is all about planning. Part of planning is establishing goals and assessment criteria. It’s at that stage where you define what SOA adoption is for your company and what criteria you’re going to use to evaluate where you’re at in the effort. Is technology infrastructure part of it? Absolutely. Are your architectural models part of it? Absolutely. Are your operational processes part of it? Absolutely. Are your governance processes part of it? Absolutely. Is your organizational structure/approach part of it? Absolutely. There’s a lot more to it than just buying a product or building a few web services.

SOA and GCM (Governance and Compliance)

SOA and GCM (Governance and Compliance)

I just listened to the latest Briefings Direct: SOA Insights podcast from Dana Gardner and friends. In this edition, the bulk of the time was spent discussing the relationship between SOA Governance and tools in the Governance and Compliance market (GCM).

I found this discussion very interesting, even if they didn’t make too many connections to the products classifying themselves as “SOA Governance” solutions. That’s not surprising though, because there’s no doubt that the marketers jumped all over the term governance in an effort to increase sales. Truth be told, there is a long, long way to go in connecting the two sets of technologies.

I’m not all that familiar with the GCM space, but the discussion did help to educate me. The GCM space is focused on corporate governance, clearly targeting the Sarbanes-Oxley space. There is no doubt that many, many dollars are spent within organizations in staying compliant with local, state, and federal (or your area’s equivalent) regulations. Executives are required to sign off that appropriate controls are in place. I’ve had experience in the financial services industry, and there’s no shortage of regulations that deal with handling investor’s assets, and no shortage of lawsuits when someone feels that their investment intent has not been followed. Corporate governance doesn’t end there, however. In addition to the external regulations, there are also the internal principles of the organization that govern how the company utilizes its resources. Controls must be put in place to provide documented assurances that resources are being used in the way they were intended. This frequently takes the form of someone reviewing some report or request for approval and signing their name on the dotted line. For these scenarios, there’s a natural relationship between analytics, business intelligence, and data warehouse products, and the GCM space appears to have ties to this area.

So where does SOA governance fit into this space? Clearly, the tools that are claiming to be players in the governance space don’t have strong ties to corporate governance. While automated checking of a WSDL file for WS-I adherence is a good thing, I don’t think it’s something that will need to show up in a SOX report anytime soon. Don’t get me wrong, I’m a fan of what these tools can offer but be cautious in thinking that the governance they claim has strong ties to your corporate governance. Even if we look at the financial aspect of projects, the tools still have a long way to go. Where do most organizations get the financial information? Probably from their project management and time accounting system. Is there integration between these tools, your source code management system, and your registry/repository? I know that BEA AquaLogic Enterprise Repository (Flashline) had the ability to track asset development costs and asset integration costs to provide an ROI for individual assets, but where do these cost numbers come from? Are they manually entered, or are they pulled directly from the systems of record?

Ultimately, the relationship between SOA Governance and Corporate Governance will come down to data. In a couple recent posts, I discussed the challenges that organizations may face with the metadata associated with SOA, as well as the management continuum. This is where these two worlds come together. I mentioned earlier that a lot of corporate governance is associated with the right people reviewing and signing off on reports. A challenge with systems of the past is their monolithic nature. Are we able to collect the right data from these systems to properly maintain appropriate controls? Clearly, SOA should break down these monoliths and increase the visibility into the technology component of the business processes. The management architecture must allow metrics and other metadata to be collected, analyzed, and reported to allow the controllers to make better decisions.

One final comment that I didn’t want to get lost. Neil Macehiter brought up Identity Management a couple times in the discussion, and I want to do my part to ensure it isn’t forgotten. I’ve mentioned “signoff” a couple times in this entry. Obviously, signoff requires identity. Where compliance checks are supported by a service-enabled GCM product, having identity on those service calls is critical. One of the things the controller needs to see is who did what. If I’m relying on metadata from my IT infrastructure to provide this information, I need to ensure that the appropriate identity stays with those activities. While there’s no shortage of rants against WS-*, we clearly will need a transport-independent way of sharing identity as it flows through the various technology components of tomorrow’s solutions.

The vendor carousel continues to spin…

The vendor carousel continues to spin…

It’s not an acquisition this time, but a rebranding/reselling agreement between BEA and AmberPoint. I was head down in my work and hadn’t seen this announcement until Google Alerts kindly informed me of a new link from James Urquhart, a blogger on Service Level Automation whose writings I follow. He asked what I think of this announcement, so I thought I’d oblige.

I’ve never been an industry analyst in the formal sense, so I don’t get invited to briefings, receive press releases, or whatever the other normal mechanisms (if there are any) that analysts use. I am best thought of as an industry observer, offering my own opinions based on my experience. I have some experience with both BEA and AmberPoint, so I do have some opinions on this. 🙂

Clearly, BEA must have customers asking about SOA management solutions. BEA doesn’t have an enterprise management solution like HP or IBM. Even if we just consider BEA products themselves, I don’t know whether they have a unified management solution across all of their products. So, there’s definitely the potential for AmberPoint technology to provide benefits to the BEA platform and customers must be asking about it. If this is the case, you may be wondering why didn’t BEA just acquire AmberPoint? First, AmberPoint has always had a strong relationship with Microsoft. I have no idea how much this results in sales for them, but clearly an outright acquisition by BEA could jeopardize that channel. Second, as I mentioned, BEA doesn’t have an enterprise management offering of which I’m aware. AmberPoint can be considered a niche management solution. It provides excellent service/SOA management, but it’s not going to allow you to also manage you physical servers and network infrastructure. So, this doesn’t wouldn’t sense on either side. BEA wouldn’t gain entry into that market, and AmberPoint would be at risk of losing customers as their message could get diluted by the rest of the BEA offerings.

As a case in point, you don’t see a lot of press about Oracle Web Services Manager these days. Oracle acquired this technology when they acquired Oblix (who acquired it when they acquired Confluent). I don’t consider Oracle a player in enterprise systems management, and as a result, I don’t think people think of Oracle when they’re thinking about Web Services Management. They’re probably more likely to think of the big boys (HP, IBM, CA) and the specialty players (AmberPoint, Progress Actional).

So, who’s getting the best out of this deal? Personally, I think this is great win for AmberPoint. It extends a sales channel for them, and is consistent with the approach they’ve taken in the past. Reselling agreements can provide strength to these smaller companies, as it builds on a perception of the smaller company as either being a market leader, having great technology, or both. On the BEA side, it does allow them to offer one-stop solutions directly in response to SOA-related RFPs, and I presume that BEA hopes it will result in more services work. BEA’s governance solution is certainly not going to work out of the box since it consists of two rebranded products (AmberPoint and HP/Mercury/Systinet) and one recently acquired product (Flashline). All of that would need to be integrated with their core execution platform. It will help BEA with existing customers who don’t want to deal with another vendor but desire an SOA management solution, but BEA has to ensure that there are integration benefits rather than just having the BEA brand.

More vendor movement…

More vendor movement…

SoftwareAG is acquiring webMethods. Interestingly, Dana Garnder’s analysis of the deal seems to imply that webMethods earlier acquisition of Infravio may have made them more attractive, but given that SoftwareAG had a solution already, CentraSite, I wouldn’t think that was the case. It is true, however, that CentraSite hasn’t received a lot of media attention. I wonder what this now means for Infravio. Clearly, SoftwareAG has two solutions in one problem space, so some consolidation is likely to occur.

Dana’s analysis points out that “bigger is better in terms of SOA solutions provider survival.” This is an interesting observation, although only time will tell. The larger best-of-breed players are expanding their offerings, but will they be viewed as platform players by consumers? It’s very interesting to look at the space at this point. At the top, you’ve got companies like IBM and Oracle who clearly are full platform vendors. It’s in the middle where things get really messy. You have everything from companies with large enough customer bases to be viewed in a strategic light to clear niche players. This includes such names BEA, HP, Sun, Tibco, Progress (which includes Sonic, Actional, Apama, and a few others), SOA Software, Iona, CapeClear, AmberPoint, Skyway Software, iWay Software, Appistry, Cassatt, Lombardi, Intalio, Vitria, Savvion, and too many more to name. Clearly, there’s plenty of other fish out there, and consolidation will continue.

What we’re seeing is that you can’t simply buy SOA. There also isn’t one single piece of infrastructure required for SOA. Full SOA adoption will require looking at nearly every aspect of your infrastructure. As a result, companies that are trying to build a marketing strategy around SOA are going to have a hard time now that the average customer is becoming more educated. That means one of two things: increase your offerings or narrow your marketing message. If you narrow the message, you run the risk of becoming insignificant, struggling to gain mindshare with the rest of the niche players. Thus, we enter the stage of eat or be eaten for all of those companies that don’t have a cash cow to keep them happy in their niche. As we’ve seen however, even the companies that do have significant recurring revenue can’t sit still. That’s life as a technology vendor, I guess.

Update: Beth Gold-Bernstein posted a very nice entry discussing this acquisition including a discussion of the areas of overlap, including the Infravio/CentraSite item. It also helped me to know where SoftwareAG now fits into this whole picture, since I honestly didn’t know all that much about them since the bulk of their business is in Europe.

Parallel Development and Integration

Parallel Development and Integration

One topic that’s come up repeatedly in my work is that of parallel development of service consumers and service providers. While over time, we would expect these efforts to become more and more independent, many organizations are still structured to be application development organizations. This typically means that services are likely identified as part of that application project, and therefore, will be developed in parallel. The efforts may all be under one project manager, or the service development efforts may be spun off as independently managed projects. Personally, I prefer the latter, as I think it increases the chances of keeping the service independent of the consumer, as well as establish clear service ownership from the beginning. Regardless of your approach, there is a need to manage the development efforts so that chaos doesn’t ensue.

To paint a picture of the problem, let’s look at a popular technique today- continuous integration. In a continuous integration environment, there are a series of automated builds and tests that are run on a scheduled basis using tools like Cruise Control, ant/Nant, etc. In this environment, shortly after someone checks in some code, a series of tests are run that will validate whether any problems have been introduced. This allows problems to be identified very early in the process, rather than waiting for some formal integration testing phase. This is a good practice, if for no other reason than encouraging personal responsibility for good testing from the developers. No one likes to be the one who breaks the build.

The challenge this creates with SOA, however, is that the service consumer and the service provider are supposed to be independent of each other. Continuous integration makes sense at the class/object level. The classes that compose a particular component of the system are tightly coupled, and should move in lock step. Service consumers and providers should be loosely coupled. They should share contract, not code. This contract should introduce some formality into the consumer/provider relationship, rather than viewing in the same light as integration between two tightly coupled classes. What I’ve found is that when the handoffs between a service development team and a consumer development team are not formalized, sooner or later, it turns into a finger-pointing exercise because something isn’t working they way they’d like, typically due to assumptions regarding the stability of the service. Often times, the service consumer is running in a development environment and trying to use a service that is also running in a development environment. The problem is that development environments, by definition, are inherently unstable. If that development environment is controlled by the automated build system, the service implementation may be changing 3 or more times a day. How can a service consumer expect consistent behavior when a service is changing that frequently? Those automated builds often include set up and take down of testing data for unit tests. The potential exists that incoming requests from a service consumer not associated with those tests may cause the unit testing to fail, because it may change the state of the system. So how do we fix the problem? I see two key activities.

First, you need to establish a stable integration environment. You may be thinking, “I already have an integration testing environment,” but is that environment used for integration with things outside of the project’s control, or is that used for integration of the major components within the project’s control. My experience has been the latter. This creates a problem. If the service development team is performing their own integration testing in the IT environment, say with a database dependency, they’re testing things they need to integrate with, not things that want to integrate with them. If the service consumer uses the service in that same IT environment, that service is probably not stable, since it’s being tested itself. You’re setting yourself up for failure in this scenario. The right way, in my opinion, to address this is to create one or more stable integration environments. This is where service (and other resources) are deployed when they have a guaranteed degree of stability and are “open for business.” This doesn’t mean they are functionally complete, only that the service manager has clearly stated what things work and what things don’t. The environment is dedicated for use by consumers of those services, not by the service development team. Creating such an environment is not easily done, because you need to manage the entire dependency chain. If a consumer invokes a service that updates a database and then pushes a message out on a queue for consumption by that original consumer, you can have a problem if that consumer is pointing at a service in one environment, but a MOM system in another environment. Overall, the purpose of creating this stable integration environment is to manage expectations. In an environment where things are changing rapidly, it’s difficult to set any expectation other than that the service may change out from underneath you. That may work fine where 4 developers are sitting in cubes next to each other, but it makes it very difficult if the service development team is in an offshore development center (or even on another floor of the building) and the consumer development team is located elsewhere. While you can manage expectations without creating new environments, creating them makes it easier to do so. This leads to the second recommendation.

Regardless of whether you have stable integration environments or not, the handoffs between consumer and provider need to be managed. If they are not, your chances of things going smoothly will go down. I recommend creating a formal release plan that clearly shows when iterations of the service will be released for integration testing. It should also show cutoff dates for when feature requests/bug reports must be received in order to make it into a subsequent iteration. Most companies are using iterative development methodologies, and this doesn’t prevent that from occurring. Not all development iterations should go into the stable environment, however. Odds are, the consumer development (especially if there’s more than one) and the service development are not going to have their schedules perfectly synchronized. As a result, the service development team can’t expect that a consumer will test particular features within a short timeframe. So, while a development iteration may occur every 2 weeks, maybe every third iteration goes into a stable integration environment, giving consumers 6 weeks to perform their integration testing. You may only have 3 or 4 stable integration releases of a service within its development lifecycle. Each release should have formal release notes and set clear expectations for service consumers. Which operations work and which ones don’t? What data sets can be used? Can performance testing be done? Again, problems happen when expectations aren’t managed. The clearer the expectations, the more smoothly things can go. It also makes it easier to see who dropped the ball when something does go wrong. If there’s no formal statement regarding what’s available within a service at any particular point in time, you’ll just get a bunch of finger pointing that will expose the poor communication that has happened.

Ultimately, managing expectations is the key to success. The burden of this falls on the shoulders of the service manager. As a service provider, the manager is responsible for all aspects of the service, including customer service. This applies to all releases of a service, not just the ones in production. Providing good customer service is about managing expectations. What do you think of products that don’t work they way you expect them to? Odds are, you’ll find something else instead. Those negative experiences can quickly undermine your SOA efforts.

Added to the blogroll…

Added to the blogroll…

I just added another blog to my blogroll, and wanted to call attention to it as it has some excellent content. According to his “about me” section, Bill Barr is an enterprise architect on the west coast with a company in the hospitality and tourism industry. His blog is titled “Agile Enterprise Architecture” and I encourage all of my readers to check it out.

New Greg the Architect

New Greg the Architect

Boy, YouTube’s blog posting feature takes a long time to show up. I tried it for the first time to create blog entries with embedded videos, but it still hasn’t shown up. Given that the majority of my readers have probably already seen it courtesy of links on ZDNet and InfoWorld, I’m caving and just posting direct links to YouTube.

The first video, released some time ago, can be viewed here. Watch this one first, if you’ve never seen it before.

The second video, just recently released and dealing with Greg’s ROI experience, can be found here.

Enjoy.