Archive for the ‘Enterprise Architecture’ Category

Horizontal and Vertical Thinking

Horizontal and Vertical Thinking

I’ve been meaning to post on this subject for some time, so it’s good that I got to the airport a little earlier than normal today. There’s nothing like blogging at 5:30 in the morning.

As I mentioned in my last entry, I just finished listening to a podcast from IT Conversations on the drive to the airport which was a discussion on user experience with Irene Au, Director of User Experience for Google. One of the questions she took from the audience dealt with the notion of having a centralized group for User Experience, or whether it should be a decentralized activity. This question is one that frequently comes up in SOA discussions, as well. Should you have a centralized service development, or should your efforts be decentralized? There’s no right or wrong answer to this question, however, it’s certainly true that your choices can impact your success. In the podcast, Irene discussed the matrixed approach at Yahoo, and how everything would up being funded by business units. This made it difficult to do activities for the greater good, such as style guides, etc. The business unit wanted to maximize their investment and have those resources focused on their activities, not someone else’s. Putting this same topic in the context of SOA, this would be the same as having user-facing application teams developing services. The challenge is that the business unit wants that user-facing application, and they want it yesterday. How do we create services that aren’t solely of value to just that application. At the opposite extreme, things can be centralized. Irene discussed the culture of open office hours at Google, and how she’ll have a line of people outside her office with their user experience questions in hand. While this may allow her to maintain a greater level of consistency, resource management can be a big challenge, as you are being pulled in multiple directions. Again, putting this in the SOA context, the risk is that in the quest for the perfect enterprise service, you can put individual project schedules at risk as they wait for the service they are dependent on. These are both extreme positions, and seldom is an organization at one extreme or the other, but usually somewhere in the middle.

In trying to tackle this problem, it’s useful to think of things as either horizontal or vertical. Horizontal concepts are ones where breadth is the more important concern. For example, infrastructure is most frequently presented as a horizontal concern. I can take a four CPU server and run just about anything I’d like on it these days, meaning it provides broad coverage across a variety of functional domains. A term frequently used these days is commodity hardware, and the notion of commoditization is a characteristic of horizontal domains. When breadth becomes more important that depth, there’s usually not many opportunities for innovation. Largely, activities become more focused on reducing the cost by leveraging economies of scale. Commoditization and standardization go hand in hand, as it’s difficult to classify something as a commodity that doesn’t meet some standard criteria. In the business world, these horizontal areas are also ones that are frequently outsourced, as all companies typically do it the same way meaning there is little room for competitive differentiation.

In trying to tackle this problem, it’s useful to think of things as either horizontal or vertical. Horizontal concepts are ones where breadth is the more important concern. For example, infrastructure is most frequently presented as a horizontal concern. I can take a four CPU server and run just about anything I’d like on it these days, meaning it provides broad coverage across a variety of functional domains. A term frequently used these days is commodity hardware, and the notion of commoditization is a characteristic of horizontal domains. When breadth becomes more important that depth, there’s usually not many opportunities for innovation. Largely, activities become more focused on reducing the cost by leveraging economies of scale. Commoditization and standardization go hand in hand, as it’s difficult to classify something as a commodity that doesn’t meet some standard criteria. In the business world, these horizontal areas are also ones that are frequently outsourced, as all companies typically do it the same way meaning there is little room for competitive differentiation.

Vertical concepts are ones where depth is the more important concern. In contrast to the commoditization associated with horizontal concerns, vertical items are ones where innovation can occur and where companies can set themselves apart from their competitors. User experience is still an area where significant differentiation can occur, so most user-facing applications fall into this category. Business knowledge, customer experience (preferably at a partnership level to have them involved in the process), are keys at this level.

By nature, vertical and horizontal concerns are orthogonal and can create tension. I have a friend who works as a user experience consultant and he once asked me about how to balance the concerns that may come from a user experience focus, clearly rooted in the vertical domains with the concerns of SOA, which are arguably focused on more horizontal concerns. There’s no easy answer to this. Just as the business must make decisions over time on where to commoditize and where to specialize, the same holds true for IT. Apple is a great example to look at, as their decision to not commoditize in their early days clearly resulted in them being relegated to niche (but still relevant) status in computer sales. Those same principles, however, to remain more vertically-focused with tight top-to-bottom controls have now resulted in their successes with their computers, iTunes, Apple TV, the iPod, and the forthcoming iPhone. There are a number of ways to be successful, although far fewer ways than there are to be unsuccessful.

When trying to slice up your functional domains into domains of services, you must certainly align it with the business goals. If there is an area of the business where they are trying to create competitive differentiation, this is probably not the best area to look for services that will have broad enterprise reuse, although it is very dependent on whether technology plays a direct role in that differentiation or an indirect role, such as whether the business to consumer interaction is solely through a website, or if it is through a company representative (e.g. a financial advisor). These areas that are closest to the end user are likely to require some degree of verticality to allow for tighter controls and differentiation. That’s not to say they own the entire solution, top to bottom, however, which would be a monolith.

As we go deeper into the stack, you should look for areas where commoditization and standardization outweighs the benefits of customization. It may begin at a domain level, such as integration across a suite of applications for a single business unit, with each successive level increasing the breadth of coverage. There is no point where the vertical solutions stop, and everything beneath it has enterprise breadth. Rather, it is a continuum of decreasing emphasis on depth and increasing emphasis on breadth. A Internet company may try to differentiate themselves in their end-user facing systems that the users interact with, allowing a large degree of autonomy for each product line. The supporting services behind those user interfaces will increase in the breadth of their scope, but still may require some degree of specialization, such as having to deal with a particular region of a country or even the world for global organizations. We then bleed into the area of “applistructure” and solutions that fall more into the support arena. A CRM system will have close ties to the end-user facing sales portal. The breadth of CRM coverage may need to span multiple lines of business, unlike the sales portal, where specialization could occur. Going deeper, we have applications that may have no ties to the end-user facing systems, but are still necessary to run a business, such as Human Resources. Interestingly, if you’re following my logic you may be thinking that these things should all be outsourced, but the truth is that many of these areas are still far from being commoditized. That’s because they involve user facing components, which brings us back to those vertical domains where customization can add value. An organization that outsources the technology side of HR, but doesn’t have an associated reduction in HR staff may have a potential conflict when they want to have specialized HR processes, but are dealing with commodity interfaces and systems. Put simply, you can’t have it both ways.

The trend continues on down the stack to the infrastructure and the world of the individual developer. If you’re truly wanting to adopt SOA from top to bottom, there should be a high degree of commoditization and standardization at this level. Organizations where solutions are still built top-to-bottom, with customized hardware platforms, source code management, programming languages, etc. are going to struggle with SOA, because their culture is vertically-oriented to an extreme.

While the speed of change, business decisions on what things are core competencies and what things are not do not change overnight. Taking an organization where each product group had its own staff (vertically-oriented) and switching it to a centralized sales organization (horizontally-oriented) is a significant cultural change, and often doesn’t go smoothly. You only need to look at the number of mergers and acquisitions that have been deemed successful (less than 50%) to understand the difficulty. Switching from vertically-focused IT solutions to horizontally-focused IT solutions is just as difficult, if not more difficult. Humans are significantly more adaptable than technology solutions, which at the core, are binary, yes/no environments. The important thing is to recognize when misalignment is occurring and take action to fix it. That’s all about governance. If users are trying to apply significant customization to a technology area that has been deemed as a commodity by the business, push back needs to occur to emphasis that the greater good takes precedence over individual needs. If IT is taking far too long to deliver a solution in an area where time to market and competitive differentiation is critical, remove the barriers and give that group more control over the solution, at the expense of broader applicability. If you don’t know what your priorities and principles are, however, for each domain, you’ll end up in and endless sequence of meetings that are rooted in opinions, rather than documented principles and behaviors desired by the organization.

Barriers to SOA Adoption

Barriers to SOA Adoption

The latest ZapFlash from ZapThink discussed what the real barrier to SOA Adoption is, and Ron points directly at IT as the source. He states:

What ZapThink is finding is that the primary barriers to SOA adoption do not come from business management … but rather from within the IT organization … too many people in the IT organization conceive SOA as a technology concept only, and as such think of SOA as just a set of technologies and infrastructure for exposing, securing, running, and managing Services.

As always, Ron walks the line of controversy with this entry. In reading the article, there’s certainly not much you can argue about as far as some generalizations of IT go. I have seen organizations that are clearly burying SOA within IT, thinking of it as just another application development technology, just as Ron describes it. On some recent work, I recently had created a slide that showed a picture of a bunch of monolithic applications and then breaking apart those monolithic into groups of services. Some may think that this is doing SOA. I’d argue that if that’s the only thing that changes, you’re probably not. In most organizations, there does need to be some fundamental changes in the way IT operates. That being said, what causes that behavior in the first place? Ron made one statement in the above quote, which I intentionally left out at first. Here’s the full text:

What ZapThink is finding is that the primary barriers to SOA adoption do not come from business management, which by and large realize the benefits of an agile, reusable, and loosely coupled architecture (even if they don’t call it that), but rather from within the IT organization …

The italicized text is what really surprised me. Previously, I had a post that said that the organizations that are claiming success with SOA probably had a culture that already had IT and business working together at a higher level. Therefore, I would expect that a business that realizes “the benefits of an agile, reusable, and loosely coupled architecture (even if they don’t call it that)” has a mature Enterprise Architecture practice, with IT having a seat at the strategic planning table. If that’s the case, it would be even more surprising to find a huge gap between IT management and architecture and the actual IT execution. That tells me that some CIO, CTO, or Chief Architect is not doing their job very well.

In organizations where SOA is buried within IT, I would have expected that IT is buried within the organization. So, while all the problems that Ron describes would be accurate, the cultural issues actually ripple beyond IT. Those cultural barriers are a huge barrier, and it’s not just an IT problem, it’s a problem for IT and the business. If the business doesn’t think strategically, which you’d think would be required in order to understand the benefits of an agile, reusable, and loosely coupled architecture, how can can IT be expected to think strategically?

My pragmatic nature tells me that there are surely cases where IT is the problem. There are also cases where the business is the problem. There are cases where both groups are the problem, and there are cases where everything is well. The only real problem is when no one recognizes the problems that exist. It’s always better to deal with your own problems before you begin finger pointing at another organization. IT can be a barrier, and Ron’s article does call out some common problems so it’s definitely worth the read. Truth be told, however, if you’re struggling with your SOA efforts, odds are that there are things that need to be fixed both within the business and IT. Don’t try to boil the ocean, but rather, understand where you’re at, the things you need to work on, and set a realistic approach in motion for doing so.

Consumer-Oriented *

Consumer-Oriented *

Brenda Michelson just posted a blog entry titled How do you “Talk to Everyone”? She’s working on a whitepaper based upon the SOA Consortium‘s Executive Summits, and had recently read Jon Udell’s post on “Talking to Everyone.” She shared the following excerpt from her work-in-progress:

“To collaborate effectively, business and IT professionals must speak a common language. Historically, business professionals have been encouraged to increase their IT literacy. This has proven successful at the project execution level. However, collaboration on strategy and architecture is a business conversation first.

“Our entry is always the process and that’s what we actually talk about – how to optimize the process, how to drive the process…When I hear business people talk about systems and they mention System A, System B, System C, I know we’re in trouble. Because basically that means to me is that we are locked into the constraints of the environment.� – CTO during SOA Executive Summit

The CIO and CTO participants encourage business-smarts in their IT organizations. IT professionals, particularly senior leaders and enterprise architects, must understand the business, and be able to relate IT capability to business value generation.”

This brought me back to the first public presentation I gave on SOA. After presenting, one of the questions asked was, “How do you talk to the business about SOA?” My answer was that I don’t talk about SOA, I talk about the business. The business discussion should create the context for a discussion about SOA, not vice versa.

The real point of this message, however, is the notion of consumer-oriented actions. Any public speaker will tell you that’s it’s important to know your audience. While I’ve never stopped and asked my audience some background questions as some presenters do, I’m sure that there are presenters who use this practice and actually do adjust their communications on the fly based on the results. Likewise, if I’m building a user interface, it’s important to know characteristics of the end user. It’s typically even better to have a real end user involved, rather than make assumptions. The same thing applies to service development. A service, first and foremost, needs to do what its consumers want it to do. Furthermore, the more it presents itself in a manner that the consumer understands, the more likely they’ll use it.

In general, I believe that any activity will have a greater chance for success if it is focused on consumption first. Unfortunately, this is seldom the path of least resistance. The past of least resistance is to put things in a manner that you, the provider, understand well. Guess what, not everyone thinks like you. It’s even likely that the majority of people don’t think like you. To be successful, you need to understand that world of your consumers. Don’t go and talk to the CEO if you don’t understand the things that he or she thinks about on a daily basis and finds important. Do your background, and position yourself for success by learning the environment of your consumers and doing your best to make it the path of least resistance for them, rather than the path of least resistance for you.

Moving from a project-based culture to a product-based culture

Moving from a project-based culture to a product-based culture

Many people have frequently stated that the biggest challenge in adoption SOA is the cultural change. That’s an easy statement to make, but how do we qualify what we mean by cultural change? Merriam-Webster provides this definition of culture:

The set of shared attitudes, values, goals, and practices that characterizes an institution or organization

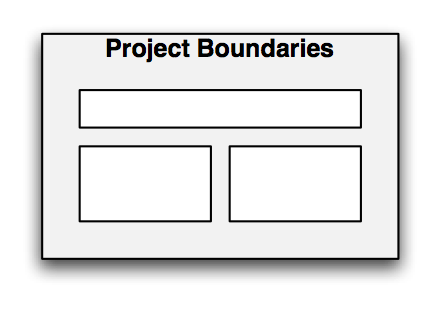

One of the attitudes and practices that arguably most organizations practice is that of the IT project. Things in IT get done by creating a project. An idea is generated by someone in the organization, typically the business side, a project is defined and funded, IT provides the solution, and the team goes on to the next project. So why is this a problem? Without projects, how would work get done? The problem that this culture creates is the dimensions of the project control all decisions. Here’s a picture that illustrates this.

Projects are wired to create things like this:

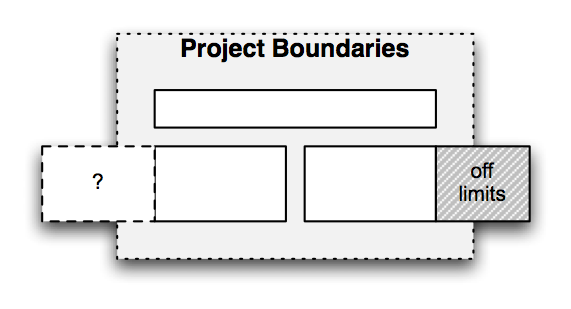

The problem is the project boundary is not a system boundary. It’s an artificial boundary. The components that comprise the project solution represent the real boundaries, but because of the project constraints, they’re unable to to set those boundaries correctly, either because they were constrained from performing appropriate analysis to figure out what they should be, or they were told that funding didn’t allow the “right” thing to be created. It looks like this:

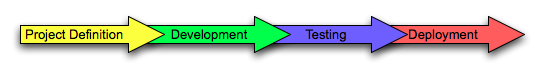

When those project boundaries become system boundaries, the result is the monolithic application, which I think we’d all agree is a bad thing. Even where the appropriate boundaries were determined, the project-based organization will likely struggle to match a team to that subcomponent for proper lifecycle management. While many organizations certainly have teams that continue to provide subsequent releases for a solution, those releases are still defined along those original project boundaries, not the correct system boundaries. Coupled with that, project-based organizations think in terms of linear, project lifecycles:

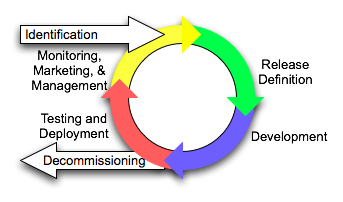

Where organizations need to go is to adopt a product-based culture based upon appropriate system boundaries, not on project boundaries. A product-based culture presumes a lifecycle like this:

Projects should be created to manage the efforts associated with a release of a product, but projects should not be the source of our system boundaries. In addition, the product-based lifecycle has that final activity of monitoring, marketing, and management, the three M’s. All too often, the project-based organization just throws things over the wall when their linear lifecycle is complete, and the only thing that happens is some alert-based monitor to notify someone when something breaks. This step needs to be formalized so that proactive monitoring takes place to increase understanding of how the service is used, including trend analysis to understand why it behaves differently (even if nothing breaks) under certain conditions. The service needs to be marketed to the community to identify new consumers and new requirements. Anyone who’s tried to achieve reuse of software within an enterprise will tell you that successful marketing is critical to this effort. Finally, all aspects of the service must be managed. This means communicating with existing consumers, updating contracts and policies as needed, sharing usage information, and doing everything possible to demonstrate that you have control over everything about this service.

This approach certainly has its challenges. From an organizational perspective, you can’t simply map a team to a given service, because the release cycle for a product may be so long that it can’t keep a team 100% occupied. A better approach is to align organizational teams around service domains, so that the team manages enough services to keep them occupied, but similar enough to allow depth of knowledge in a given area. These could be horizontal domains, focused on infrastructure libraries, or they could be vertical domains, focused on areas of business capability. Odds are your organization will require both, just as it likely has separate teams today that specialize in technical infrastructure typically purchased from a vendor from groups that specialize in more vertical application development.

If SOA could be done as a project, these organizations would be doing it. The problem is that it can’t. Many organizations are tying SOA to some major initiative which has significant breadth of scope such that the right boundaries for services can be determined, however, if they don’t find a way to transition to a more product-like development model rather than a project-like development model, they’ll still struggle after that initiative is complete.

Privacy of information

Privacy of information

I saw this story about corporate data slipping out via Google Calendar and it hit home. I’m not a Google Calendar user, but I had briefly looked into it a little while ago when trying to figure out a way to give my wife visibility to my work calendar. If I recall, there was no way that I could easily give her a unique user id and password to be able to subscribe to my calendar via iCal. I certainly didn’t want to open it up to the general public to be able to do so.

I’m willing to bet that many of the corporate employees that were using Google Calendar were doing so to integrate their work schedule and their personal schedules, whether for their own use, their spouse’s use, or others. This is even more challenging for consultants, who probably have their corporate schedule from their consulting firm, plus their personal schedules, plus the corporate scheduling system from their clients. The consumer of this information (you and me) would like to manage it all in one spot, but the systems today simply don’t allow that to happen.

Let’s suppose, theoretically, that I could tell the corporate scheduling system to make my schedule available for synchronization with my calendar at home. That does create risks of exposing sensitive information as described in the article, such as dial-in numbers and passcodes, project names, etc. In reality, all I may need to know is whether the time is available or not. If I’m making it available to my wife, I’m really only interested in letter her know whether it’s okay to interrupt me at that time. To support this, we really need some fine-grained access control based on roles. That requires a couple things. First, it requires that we know the identity of the consumer of the information. That identity gets mapped to a role which provides appropriate context for the request. Secondly, I need the ability to map data elements to roles. It may even mean involve data manipulation rules. I don’t know of any calendar system that allows me to designate something as “okay to interrupt”, so I’d have to put that information in some other field. The situation quickly gets complicated.

This is a very simple, everyday case that we can all relate to, however, if we look at the overall use of information, it’s extremely difficult to understand all the different ways a given piece of information may be used and the roles and policies associated with each context. That doesn’t mean we should ignore it, however. There is clear room for improvement in what Google Calendar allows an individual calendar owner to do, just as there is clear room for improvement in corporate information security.

External consumers and providers

External consumers and providers

James McGovern, in his links entry for April 11th posted this comment in regards to my entry on what SOA adoption actually means:

“A measurement that would be interesting is to ask enterprises how many services do you have that are consumed outside of your enterprise. The numbers would be dramatically lower…”

As I thought about this, it became more and more interesting. First, I definitely agree that the number of services is going to be dramatically lower, unless your company is already a service provider (think ASP), in which case, then it should constitute the majority of your service portfolio. What about other verticals, however? Certainly supply chain interactions will involve external entities. Truth be told, there’s lot of potential for interactions with partner companies. How many companies outsource payroll processing to ADP or someone else? I’d venture a guess that there are probably areas for commodity services in every vertical. Over time, things that once were competitive differentiators become commodities. Once that happens, a marketplace opens up for commodity providers that focus on operational excellence and low cost, and the companies that prefer to focus on customer service get rid of their homegrown infrastructure and leverage the commodity provider. Guess what, when that happens, the potential now exists for service interactions. I recently presented some introductory information on service concepts and described business services as services that both ones that represent the primary business functions as well as ones that support the primary business such as HR, payroll, etc. Technology clearly plays a big role in both.

You may be thinking, “No arguments on what you said, but James asked about services consumed by outsiders, not provided by outsiders.” Quite true, but again, I’d be willing to bet that the vast majority of these B2B interactions will require bi-directional communications. It may be the case that 90% of the time, the partner acts in the service provider role, but odds are that some of that processing will require them having the ability to make service calls back to you. At a minimum, some form of events should be flowing back into your infrastructure. The more information flow can be a circle, rather than a one-way line, the greater the potential for leveraging emerging technologies like CEP for continued innovation. If the information only flows one way, you severely restrict your ability to innovate based on that information.

Aside:James also posted some musings on Open Source and the possibilities of it playing a role in commodity vertical applications yesterday. If that happened, there would certainly have potential implications. It probably wouldn’t take long for someone to create a hosted solution for these open source offerings, again creating the potential for service interactions between the two companies.

The end result of my thinking on this is that if your thinking on SOA is constrained to inside your firewall, it won’t be very long at all before you need to extend that thinking, both as a consumer of services provided from the outside as well as a provider of services that will be consumed by the outside. Companies that make the claim that they’ve “adopted SOA” should have a view that encompasses all of it, regardless of whether their core business is being a service provider or not.

Parallel Development and Integration

Parallel Development and Integration

One topic that’s come up repeatedly in my work is that of parallel development of service consumers and service providers. While over time, we would expect these efforts to become more and more independent, many organizations are still structured to be application development organizations. This typically means that services are likely identified as part of that application project, and therefore, will be developed in parallel. The efforts may all be under one project manager, or the service development efforts may be spun off as independently managed projects. Personally, I prefer the latter, as I think it increases the chances of keeping the service independent of the consumer, as well as establish clear service ownership from the beginning. Regardless of your approach, there is a need to manage the development efforts so that chaos doesn’t ensue.

To paint a picture of the problem, let’s look at a popular technique today- continuous integration. In a continuous integration environment, there are a series of automated builds and tests that are run on a scheduled basis using tools like Cruise Control, ant/Nant, etc. In this environment, shortly after someone checks in some code, a series of tests are run that will validate whether any problems have been introduced. This allows problems to be identified very early in the process, rather than waiting for some formal integration testing phase. This is a good practice, if for no other reason than encouraging personal responsibility for good testing from the developers. No one likes to be the one who breaks the build.

The challenge this creates with SOA, however, is that the service consumer and the service provider are supposed to be independent of each other. Continuous integration makes sense at the class/object level. The classes that compose a particular component of the system are tightly coupled, and should move in lock step. Service consumers and providers should be loosely coupled. They should share contract, not code. This contract should introduce some formality into the consumer/provider relationship, rather than viewing in the same light as integration between two tightly coupled classes. What I’ve found is that when the handoffs between a service development team and a consumer development team are not formalized, sooner or later, it turns into a finger-pointing exercise because something isn’t working they way they’d like, typically due to assumptions regarding the stability of the service. Often times, the service consumer is running in a development environment and trying to use a service that is also running in a development environment. The problem is that development environments, by definition, are inherently unstable. If that development environment is controlled by the automated build system, the service implementation may be changing 3 or more times a day. How can a service consumer expect consistent behavior when a service is changing that frequently? Those automated builds often include set up and take down of testing data for unit tests. The potential exists that incoming requests from a service consumer not associated with those tests may cause the unit testing to fail, because it may change the state of the system. So how do we fix the problem? I see two key activities.

First, you need to establish a stable integration environment. You may be thinking, “I already have an integration testing environment,” but is that environment used for integration with things outside of the project’s control, or is that used for integration of the major components within the project’s control. My experience has been the latter. This creates a problem. If the service development team is performing their own integration testing in the IT environment, say with a database dependency, they’re testing things they need to integrate with, not things that want to integrate with them. If the service consumer uses the service in that same IT environment, that service is probably not stable, since it’s being tested itself. You’re setting yourself up for failure in this scenario. The right way, in my opinion, to address this is to create one or more stable integration environments. This is where service (and other resources) are deployed when they have a guaranteed degree of stability and are “open for business.” This doesn’t mean they are functionally complete, only that the service manager has clearly stated what things work and what things don’t. The environment is dedicated for use by consumers of those services, not by the service development team. Creating such an environment is not easily done, because you need to manage the entire dependency chain. If a consumer invokes a service that updates a database and then pushes a message out on a queue for consumption by that original consumer, you can have a problem if that consumer is pointing at a service in one environment, but a MOM system in another environment. Overall, the purpose of creating this stable integration environment is to manage expectations. In an environment where things are changing rapidly, it’s difficult to set any expectation other than that the service may change out from underneath you. That may work fine where 4 developers are sitting in cubes next to each other, but it makes it very difficult if the service development team is in an offshore development center (or even on another floor of the building) and the consumer development team is located elsewhere. While you can manage expectations without creating new environments, creating them makes it easier to do so. This leads to the second recommendation.

Regardless of whether you have stable integration environments or not, the handoffs between consumer and provider need to be managed. If they are not, your chances of things going smoothly will go down. I recommend creating a formal release plan that clearly shows when iterations of the service will be released for integration testing. It should also show cutoff dates for when feature requests/bug reports must be received in order to make it into a subsequent iteration. Most companies are using iterative development methodologies, and this doesn’t prevent that from occurring. Not all development iterations should go into the stable environment, however. Odds are, the consumer development (especially if there’s more than one) and the service development are not going to have their schedules perfectly synchronized. As a result, the service development team can’t expect that a consumer will test particular features within a short timeframe. So, while a development iteration may occur every 2 weeks, maybe every third iteration goes into a stable integration environment, giving consumers 6 weeks to perform their integration testing. You may only have 3 or 4 stable integration releases of a service within its development lifecycle. Each release should have formal release notes and set clear expectations for service consumers. Which operations work and which ones don’t? What data sets can be used? Can performance testing be done? Again, problems happen when expectations aren’t managed. The clearer the expectations, the more smoothly things can go. It also makes it easier to see who dropped the ball when something does go wrong. If there’s no formal statement regarding what’s available within a service at any particular point in time, you’ll just get a bunch of finger pointing that will expose the poor communication that has happened.

Ultimately, managing expectations is the key to success. The burden of this falls on the shoulders of the service manager. As a service provider, the manager is responsible for all aspects of the service, including customer service. This applies to all releases of a service, not just the ones in production. Providing good customer service is about managing expectations. What do you think of products that don’t work they way you expect them to? Odds are, you’ll find something else instead. Those negative experiences can quickly undermine your SOA efforts.

Added to the blogroll…

Added to the blogroll…

I just added another blog to my blogroll, and wanted to call attention to it as it has some excellent content. According to his “about me” section, Bill Barr is an enterprise architect on the west coast with a company in the hospitality and tourism industry. His blog is titled “Agile Enterprise Architecture” and I encourage all of my readers to check it out.

New Greg the Architect

New Greg the Architect

Boy, YouTube’s blog posting feature takes a long time to show up. I tried it for the first time to create blog entries with embedded videos, but it still hasn’t shown up. Given that the majority of my readers have probably already seen it courtesy of links on ZDNet and InfoWorld, I’m caving and just posting direct links to YouTube.

The first video, released some time ago, can be viewed here. Watch this one first, if you’ve never seen it before.

The second video, just recently released and dealing with Greg’s ROI experience, can be found here.

Enjoy.

The management continuum

The management continuum

Mark Palmer of Apama continued his series of posts on myths around the EDA/CEP space, with number 3: BAM and BPM are Converging. Mark hit on a subject that I’ve spoken with clients about, however, I don’t believe that I’ve ever posted on it.

Mark’s premise is that it’s not BAM and BPM that are converging, it’s BAM and EDA. Converging probably isn’t the right word here, as it implies that the two will become one, which certainly isn’t the case. That wasn’t Mark’s point, either. His point was that BAM will leverage CEP and EDA. This, I completely agree with.

You can take a view on our solutions like the one below. At higher levels, the concepts we’re dealing with are more business-centric. At lower levels, the concepts are more technology-centric. Another way of looking at it is that at the higher levels, the products involved would be specific to the line of business/vertical we’re dealing with. At the lower levels, the products involved would be more generic, applicable to nearly any vertical. For example, an insurance provider may have things like quoting and underwriting at the top, but at the bottom, we’d have servers, switches, etc. Clearly, the use of servers are not specific to the insurance industry.

All of these platforms require some form of management and monitoring. At the lowest levels of the diagram, we’re interested in traditional Enterprise Systems Management (ESM). The systems would be getting data on CPU load, memory usage, etc. and technologies like SNMP would be involved. One could certainly argue that these ESM tools are very event-drvien. The collection of metrics and alerts is nearly always done asynchronously. If we move up the stack, we get to business activity monitoring. The interesting thing is that the fundamental architecture of what is needed does not change. Really, the only thing that changes is the semantics of the information that needs to get pushed out. Rather than pushing CPU load, I may be pushing out the number of auto insurance quotes requested and processed. This is where Mark is right on the button. If the underlying systems are pushing out events, whether at a technical level or at a business level, there’s no reason why CEP can’t be applied to that stream to deliver back valuable information to the enterprise, or even better, coming full circle and invoking some automated process to take action.

I think that the most important takeaway on this is that you have to be thinking from an architectural standpoint as you build these things out. This isn’t about running out and buying a BAM tool, a BPM tool, a CEP tool, or anything else. What metrics are important? How will the metrics be collected? How do you want to perform analytics (is static analysis against a centralized store enough, or do you need dynamic analysis in realtime driven by changing business rules)? What do you want to do with the results of that analysis? Establishing a management architecture will help you make the right decisions on what products you need to support it.

SOA Consortium

SOA Consortium

The SOA Consortium recently gave a webinar that presented their Top 5 Insights based upon a series of executive summaries they conducted. Richard Mark Soley, Executive Director of the SOA Consortium, and Brenda Michelson of Elemental Links were the presenters.

A little background. The SOA Consortium is a new SOA advocacy group. As Richard Soley put it during the webinar, they are not a standards body, however, they could be considered a source of requirements for the standards organizations. I’m certainly a big fan of SOA advocacy and sharing information, if that wasn’t already apparent. Interestingly, they are a time-boxed organization, and have set an end date of 2010. That’s a very interesting approach, especially for a group focused on advocacy. It makes sense, however, as the time box represents a commitment. 12 practitioners have publicly stated their membership, along with the four founding sponsors, and two analyst firms.

What makes this group interesting is that they are interested in promoting business-driven SOA, and dispelling the notion that SOA is just another IT thing. Richard had a great anecdote of one CIO that had just finished telling the CEO not to worry about SOA, that it was an IT thing and he would handle it, only to attend one of their executive summits and change course.

The Top 5 insights were:

- No artificial separation of SOA and BPM. The quote shown in the slides was, “SOA, BPM, Lean, Six Sigma are all basically on thing (business strategy & structure) that must work side by side.” They are right on the button on this one. The disconnect between BPM efforts and SOA efforts within organizations has always mystified me. I’ve always felt that the two go hand in hand. It makes no sense to separate them.

- Success requires business and IT collaboration. The slide deck presented a before and after view, with the after view showing a four-way, bi-directional relationship between business strategy, IT strategy, Enterprise Architecture, and Business Architecture. Two for two. Admittedly, as a big SOA (especially business-driven SOA) advocate, this is a bit of preaching to the choir, but it’s great to see a bunch of CIOs and CTOs getting together and publicly stating this for others to share.

- On the IT side, SOA must permeate the organization. They recommend the use of a Center of Excellence at startup, which over times shifts from a “doing” responsibility to a “mentoring” responsibility, eventually dissolving. Interestingly, that’s exactly what the consortium is trying to do. They’re starting out with a bunch of people who have had significant success with SOA, who are now trying to share their lessons learned and mentor others, knowing that they’ll disband in 2010. I think Centers of Excellence can be very powerful, especially in something that requires the kind of cultural change that SOA will. Which leads to the next point.

- There are substantial operational impacts, but little industry emphasis. As we’ve heard time and time again, SOA is something you do, not something you buy. There are some great quotes in the deck. I especially liked the one that discussed the horizontal nature of SOA operations, in contrast to the vertical nature (think monolithic application) of IT operations today. The things concerning these executives are not building services, but versioning, testing, change management, etc. I’ve blogged a number of times on the importance of these factors in SOA, and it was great to hear others say the same thing.

- SOA is game changing for application providers. We’ve certainly already seen this in action with activities by SAP, Oracle, and others. What was particularly interesting in the webinar was that while everyone had their own opinion on how the game will change, all agreed that it will change. Personally, I thought these comments were very consistent with a post I made regarding outsourcing a while back. My main point was that SOA, on its own, may not increase or decrease outsourcing, but it should allow more appropriate decisions and hopefully, a higher rate of success. I think this applies to both outsourcing, as well as to the use of packaged solutions installed within the firewall.

Overall, this was a very interesting and insightful webinar. You can register and listen to a replay of it here. I look forward to more things to come from this group.

Reference Architectures and Governance

Reference Architectures and Governance

In the March 5th issue of InfoWorld, I was quoted in Phil Windley’s article, “Teaming Up For SOA.” One of the quotes he used was the following:

Biske also makes a strong argument for reference architectures as part of the review process. “Architectural reviews tie the project back to the reference architecture, but if there’s no documentation that project can be judged against, the architectural review won’t have much impact.”

My thinking on this actually came from a past colleague. We were discussing governance, and he correctly pointed out that it is unrealistic to expect benefits from a review process when the groups presented have no idea what they are being reviewed against. The policies need to be stated in advance. Imagine if your town had no speed limit signs, yet the police enforced a speed limit. What would be your chances of getting a ticket? What if your town had a building code, but the only place it existed was in the building inspector’s head. Would you expect your building to pass inspections? What would be your feelings toward the police or the inspector after you received a ticket or were told to make significant structural changes?

If you’re going to have reviews that actually represent an approval to go forward, you need to have documented policies. At the architectural level, this is typically done through the use of reference architectures. The challenge is that there is no accepted norm for what a reference architecture should contain. Rather than get into a semantic debate over the differences between a reference architecture, a reference model, a conceptual architecture, and any number of other terms that are used, I prefer to focus on what is important- giving guidance to the people that need it.

I use the term solution architect to refer to the person on a project that is responsible for the architecture of the solution. This is the primary audience for your reference material. There are two primary things to consider with this audience:

- What policies need to be enforced?

- What deliverable(s) does the solution architect need to produce?

Governance does begin with policies, and I put that one first for a reason. I worked with an organization that was using the 4+1 view model from Philippe Kruchten for modeling architecture. The problem I had was that the projects using this model were not adequately able to convey the services that would be exposed/utilized by their solution. The policy that I wanted enforced at the architecture review was that candidate services had been clearly identified, and potential owners of those services had been assigned. If the solution architecture can’t convey this, it’s a problem with the solution architecture format, not the policy. If you know your policies, you should then create your sample artifacts to ensure that those policies can be easily enforced through a review of the deliverable(s). This is where the reference material comes into play, as well. In this scenario, the purpose of the reference material is to assist the solution architect in building the required deliverable(s). Many architects may create future state diagrams that may be accurate representations, but wind up being very difficult to use in a solution architecture context. The projects are the efforts that will get you to that future state, so if the reference material doesn’t make sense to them, it’s just going to get tossed aside. This doesn’t bode well for the EA group, as it will increase the likelihood that they are seen as an ivory tower.

When creating this material, keep in mind that there are multiple views of a system, and a solution architect is concerned with all of them. I mentioned the 4+1 view model. There’s 5 views right there, and one view it doesn’t include is a management view (operational management of the solution). That’s at least 6 distinct views. If your reference material consists of one master Visio diagram, you’re probably trying to convey too much with it, and as a result, you’re not conveying anything other than complexity to the people that need it. Create as many diagrams and views as necessary to ensure compliance. Governance is not about minimizing the number of artifacts involved, it’s about achieving the desired behavior. If achieving desired behavior requires a number of diagrams and models, so be it.

Finally, architectural governance is not just about enforcing policies on projects. In Phil’s articles some of my quotes also alluded to the project initiation process. EA teams have the challenge of trying to get the architectural goals achieved, but often times without the ability to directly create and fund projects themselves. In order to achieve their goals, the current state and future state architectures must also be conveyed to the people responsible for IT Governance. This is an entirely different audience, one whom the reference architectures created for the solution architects may be far too technical in nature. While it would minimize the work of the architecture team to have one set of reference material that would work for everyone, that simply won’t be the case. Again, the reference material needs to fit the audience. Just as a good service should fit the needs of its consumers, the reference material produced by EA must do the same.

ROI and SOA

ROI and SOA

Two ZDNet analysts, Dana Gardner and Joe McKendrick, have had recent posts (I’ve linked their names to the specific posts) regarding ROI and SOA. This isn’t something I’ve blogged on in the past, so I thought I’d offer a few thoughts.

First, let’s look at the whole reason for ROI in the first place. Simply put, it’s a measurement to justify investment. Investment is typically quanitified in dollars. That’s great, now we need to associate dollars with activities. Your staff has salaries or bill rates, so this shouldn’t be difficult, either. Now is where things get complicated, however. Activities are associated with projects. SOA is not a project. An architecture is a set of constraints and principles that guide an approach to a particular problem, but it’s not the solution itself. Asking for ROI on SOA is similar to asking for ROI on Enterprise Architecture, and I haven’t seen much debate on that. That being said, many organizations still don’t have EA groups, so there are plenty of CIOs that may still question the need for it as a formal job classification. Getting back to the topic, we can and do estimate costs associated with a project. What is difficult, however, is determining the cost at a fine-grained level. Can you determine the cost of developing services in support of that project accurately? In my past experience, trying to use a single set of fine-grained activities for both project management and time accounting was very difficult. Invariably, the project staff spent time that was focused on interactions that were needed to determine what the next step was. These actions never map easily into a standard task-based project plan, and as a result, caused problems when trying to charge time. (Aside: For an understanding on this, read Keith Harrison-Broninski’s book Human Interactions or check out his eBizQ blog.) Therefore, it’s going to be very difficult to put a cost on just the services component of a project, unless it’s entire scope of the project, which typically isn’t the case.

Looking at the benefits side of the equation, it is certainly possible to quantify some expected benefits of the project, but again, only a certain level. If you’re strictly looking at IT, your only hope of coming up with ROI is to focus on cost reduction. IT is typically a cost center, with at best, an indirect impact on revenue generation. How are costs reduced? This is primarily done by reducing maintenance costs. The most common approach is through a reduction in the number of vendor products involved and/or a reduction in the number of vendors involved. More stuff from fewer vendors typically means more bundling and greater discounts. There are other options, such as using open source products with no licensing fees, or at least discounted fees. You may be asking, “What about improved productivity?” This is an indirect benefit, at best. Why? Unless there is a reduction in headcount, the cost to the organization is fixed. If a company is paying a developer $75,000 / year, that developer gets that money regardless of how many projects get done and what technologies are used. Theoretically, however, if more projects are completed within a given time, you’d expect that there is a greater potential for revenue. That revenue is not based upon whether SOA was used or not, it’s based upon the relevance of that project to business efforts.

So now we’re back to the promise of IT – Business agility. For a given project, ROI should be about measuring the overall project cost (not specific actions within it) plus any ongoing costs (maintenance) against business benefits (revenue gain) and ongoing cost reduction. So where will we get the best ROI? We’ll get the best ROI by picking projects with the best business ROI. If you choose a project that simply rebuilds an existing system using service technologies, all you’ve done is incurred cost unless those services now create the potential for new revenue sources (a business problem, not a technology problem), or cost consolidation. Cost consolidation can come from IT on its own through reduction in maintenance costs, although if you’re replacing one homegrown system with another, you only reduce costs if you reduce staff. If you get rid of redundant vendor systems, clearly there should be a reduction in maintenance fees. If you’re shooting for revenue gain, however, the burden falls not to IT, but to the business. IT can only control the IT component of the project cost and we should always be striving to reduce that through reuse and improved tooling. Ultimately, however, the return is the responsibility of the business. If the effort doesn’t produce the revenue gain due to inaccurate market analysis, poor timing, or anything else, that’s not the fault of SOA.

There are two last points I want to make, even though this entry has gone longer than I expected. First, Dana made the following statement in his post:

So in a pilot project, or for projects driven at the departmental level, SOA can and should show financial hard and soft benefits over traditional brittle approaches for applications that need integration and easy extensibility (and which don’t these days?).

I would never expect a positive ROI on a pilot project. Pilots should be run with the expectation that there are still unknowns that will cause hiccups in the project, causing it to run at a higher cost that a normal project. A pilot will then result in a more standardized approach for subsequent projects (the extend phase in my maturity model discussions) where the potential can be realized. Pilots should be a showcase for the potential, but they may not be the project that realizes it, so be careful in what you promise.

Dana goes on to discuss the importance of incremental gains from every project, and this I agree with. As he states, it shouldn’t be an “if we build it, they will come” bet. The services you choose to build in initial projects should be ones that you have a high degree of confidence that they will either be reused, or, that they will be modified in the future but where the more fine-grained boundaries allow those modifications to be performed at a lower cost than previously the case.

Second, SOA is an exercise in strategic planning. Every organization has staff that isn’t doing project work, and some subset of that staff is doing strategic planning, whether formally or informally. Without the strategic plan, you’ll be hard pressed to have accurate predictions on future gains, thus making all of your ROI work pure speculation, at best. There’s always an element of speculation in any estimate, but it shouldn’t be complete speculation. So, the question then is not about separate funding for SOA. It’s about looking at what your strategic planners are actually doing. Within IT, this should fall to Enterprise Architecture. If they’re not planning around SOA, then what are they planning? If there are higher priority strategic activities that they are focused on, fine. SOA will come later. If not, then get to work. If you don’t have enterprise architecture, then who in IT is responsible for strategic planning? Put the burden on them to establish the SOA direction, at no increase in cost (presuming you feel it is higher priority than their other activities). If no one is responsible, then your problem is not just SOA, it’s going to be anything of a strategic nature.

Is the SOA Suite good or bad?

Is the SOA Suite good or bad?

I haven’t listed to the podcast yet, but Joe McKendrick posted a summary of the discussion in a recent Briefings Direct SOA Insights conversation organized by Dana Gardner. In his entry, Joe asks whether vendors are promoting an oxymoron in offering SOA suites. He states:

“Jumbo shrimp” and “government organization” are classic examples of oxymorons, but is the idea of an “SOA suite” also just as much a contradiction of terms? After all, SOA is not supposed to be about suites, bundles, integration packages, or anything else that smacks of vendor lock-in.

“The big guys — SAP, Oracle, Microsoft, webMethods, lots of software vendors — are saying, ‘Hey, we provide a bigger, badder SOA suite than the next guy,'” Jim Kobelius pointed out. “That raises an alarm bell in my mind, or it’s an anomaly or oxymoron, because when you think of SOA, you think of loose coupling and virtualization of application functionality across a heterogeneous environment. Isn’t this notion of a SOA suite from a single vendor getting us back into the monolithic days of yore?”

Personally, I have no issue with SOA suites. The big vendors are always going to go down this route, and if anything, it simply demonstrates just how far we have to go on the open integration front. If you follow this blog, you know that I’ve discussed SOA for IT. SOA for IT, in my mind, is all about integration across the technology infrastructure at a horizontal level, not a vertical level. SOA for business is concerned about the vertical level semantics of the business, and allowing things to integrate at a business sense. SOA for IT is about integration at the technical level. Can my Service Management infrastructure talk to my Service Execution infrastructure? Can my Service Execution infrastructure talk to my Service Mediation infrastructure? Can my Service Mediation infrastructure talk to my Service Management infrastrucutre? The list goes on. Why is their still a need for these SOA suites? Simply put, we still lack standards for communication between these platforms. It’s one thing to say all of the infrastructure knows how to speak with a UDDI v3 registry. It’s another thing to have the infrastructure agree on the semantics of the metadata placed in a registry/repository (note, there’s no standard repository API), and leverage that information successfully across a heterogeneous set of environments. The smaller vendors try to form coalitions to make this a reality, as was the case with Systinet’s Governance Interoperability Framework, but as they get swallowed up by the big fish, what happens? IBM came out with WebSphere Registry/Repository and it introduced new, proprietary APIs. Competitive advantage for an all IBM environment? Absolutely. If I don’t have an all IBM environment, am I that much worse off however? If I have AmberPoint or Actional for SOA management, I’m still dealing with their proprietary interfaces and policy definitions, so vendor lock-in still exists. I’m just locked in to multiple vendors, rather than one.

The only way this gets fixed is if customers start demanding open standards for technology integration as part of their evaluation criteria. While the semantics of the information exchange may not exist yet, you can at least ask whether or not the vendor exposes management interfaces as services. Put another way, the internal architecture of the product needs to be consistent with the internal architecture of your IT systems. If you desire to have separation of management from enforcement, then your vendor products must expose management services. If the only way to configure their product is through a web-based user interface or by attempting to directly manipulate configuration files, this is going to be very costly for you if you’re trying to reduce the number of independent management console that operations needs to deal with. Even if it’s all IBM, Oracle, Microsoft, or whoever, the internal architecture of that suite needs to be consistent with your vendor-independent target architecture. If you haven’t taken the time to develop one, then you’re allowing the vendors to push their will on you.

Let’s use the city planning analogy. A suite vendor is akin to the major developer. Do the city planners simply say, “Here’s your 80,000 acres, have fun?” That probably wouldn’t result in a good deal for the city. Taking the opposite extreme, the city doesn’t want individual property owners to do whatever they want, either. Last year, there was article about a nearby town that had somehow managed to allow an adult store to set up shop next door to a daycare center in a strip mall. Not good. The right approach, whether you want to have a diverse set of technologies, or a very homogenous set is to keep the power in the hands of the planners, and that is done through architecture. If you can remain true to your architecture with a single vendor? Great. If you prefer to do it with multiple vendors, that’s great at well. Just make sure that you’re setting the rules, not them.

Models of EA

Models of EA

One thing that I’ve noticed recently is that there is no standard approach to Enterprise Architecture. Some organizations may have Enterprise Architecture on the organizational chart, other organizations may merely have an architectural committee. One architecture team may be all about strategic planning, while another is all about project architecture. Some EA teams may strictly be an approval body. I think the lack of a consistent approach is an indicator of the relative immaturity of the discipline. While groups like Shared Insights have been putting on Enterprise Architecture conferences for 10 years now, there are still many enterprises that don’t even have an EA team.

So what is the right approach to Enterprise Architecture? As always, there is no one model. The formation of an EA team is often associated with some pain point in the enterprise. In some organizations, there may be a skills gap necessitating the formation of an architecture group that can fan out across multiple projects, providing project guidance. A very common pain point is “technology spaghetti.â€? That is, over time the organization has acquired or developed so many technology solutions that the organization may have significant redundancy and complexity. This pain point can typically result in one of two approaches. The first is an architecture review board. The purpose of the board is to ensure that new solutions don’t make the situation any worse, and if possible, they make it better. The second approach is the formation of an Enterprise Architecture group. The former doesn’t appear on the organization chart. The latter does, meaning it needs day to day responsibilities, rather than just meeting when an approval decision is needed. Those day to day activities can be the formation of reference architectures and guiding principles, or they could be project architecture activities like the first scenario discussed. Even in these scenarios, however, Enterprise Architecture still doesn’t have the teeth it needs. Reference architectures and/or guiding principles may have been created, but these end state views will only be reached if a path is created to get there. This is where strategic planning comes into play. If the EA team isn’t involved in the strategic planning process, then they are at the mercy of the project portfolio in achieving the architectural goals. It’s like being the coach or manager of a professional sports team but having no say whatsoever in the player personnel decisions. The coach will do the best they can, but if they were handed players who are incompatible in the clubhouse or missing key skills necessary to reach the playoffs, they won’t get there.

You may be thinking, “Why would anyone ever want an EA committee over a team?â€? Obviously, organizational size can play a factor. If you’re going to form a team, there needs to enough work to sustain that team. If there isn’t, then EA becomes a responsibility of key individuals that they perform along with their other activities. Another scenario where a committee may make sense is where the enterprise technology is largely based on one vendor, such as SAP. In this case, the reference architecture is likely to be rooted in the vendor’s reference architecture. This results in a reduction of work for Enterprise Architecture, which again, has the potential to point to a responsibility model rather than a job classification.

All in all, regardless of what model you choose for your organization, I think an important thing to keep in mind is balance. An EA organization that is completely focused on reference architecture and strategic planning runs the risk of becoming an ivory tower. They will become disconnected from the projects that actually make the architecture a reality. The organization runs a risk that a rift will form between the “practitionersâ€? and the “strategists.â€? Even if the strategists have a big hammer for enforcing policy, that still doesn’t fix the cultural problems which can lead to job dissatisfaction and staff turnover. On the flip slide, if the EA organization is completely tactical in nature, the communication that must occur between the architects to ensure consistency will be at risk. Furthermore, there will still be no strategic plan for the architecture, so decisions will likely be made according to short term needs dominated by individual projects. The right approach, in my opinion, is to maintain a balance of strategic thinking and tactical execution within your approach to architecture. If the “officialâ€? EA organization is focused on strategic planning and reference architecture, they must come up with an engagement model that allows bi-directional communication with the tactical solution architects to occur often. If the EA team is primarily tasked with tactical solution architecture, then they must establish an engagement model with the IT governance managers to ensure that they have a presence at the strategic planning table.