Archive for the ‘Enterprise Architecture’ Category

Teaming Up for SOA

Teaming Up for SOA

I recently “teamed up” with Phil Windley. He interviewed me for his latest InfoWorld article on SOA Governance which is now available online, and is in the March 5th print issue. Give it a read and let me know what you think. I think Phil did a great job in articulating a lot of the governance challenges that organizations run into. Of the areas where I was quoted, the one that I think is a significant culture change is the funding challenge. It’s not just about getting funding for shared services which is a challenge on its own. It’s also a challenge of changing the way that organizations make decisions to include architectural elements in the decision. Many organizations that I have dealt with all tend to be schedule driven. That is, the least flexible element of the project is schedule. Conversely, the thing that always gives is scope. Unfortunately, it’s not usually visible scope, it’s usually the difference in taking the quickest path (tactical) versus the best path (strategic). If you’re one of many organizations trying to do grass roots SOA, this type of IT governance makes life very difficult as the culture rewards schedule success, not architectural success. It’s a big culture shift. Does your Chief Architect have a seat at the IT Governance table?

Anyway, I hope you enjoy the article. Feel free to post your questions here, and I’d be happy to followup.

Metrics, metrics, metrics

Metrics, metrics, metrics

James McGovern threw me a bone in a recent post, and I’m more than happy to take it. In his post, “Why Enterprise Architects need to noodle metrics…” he asks:

Hopefully bloggers such as Robert McIlree, Scott Mark, Todd Biske and others would be willing to share not only successes within their own enterprise when it comes to metrics but also any unintended consequences in terms of collecting them.

I’m a big, big fan of instrumentation. One of the projects that I’m most proud of was when we built a custom application dashboard using JMX infrastructure (when JMX was in its infancy) for a pretty large web-based system. The people that used it really enjoyed the insight it gave them into the run-time operations of the system. I personally didn’t get to use it, as I was rolled onto another project, but the operations staff loved it. Interesting, my first example of metrics being useful comes from that project, but not from the run time management. It came from our automated build system. At the time, we had an independent contractor who was acting as a project management / technical architecture mentor. He would routinely visit the web page for the build management system and record the number of changed files for each build. This was a metric that the system captured for us, but no one paid much attention to it. He started posting graphs showing the number of changed files over time, and how we had spikes before every planned iteration release. He let us know that those spikes disappeared, we weren’t going live. Regardless of the number of defects logged, the significant amount of change before a release was a red flag for risk. This message did two things: first, it kept people from working to a date, and got them to just focus on doing their work at an appropriate pace. Secondly, I do think it helped up release a more stable product. Fewer changes meant more time for integration testing within the iteration.

The second area where metrics have come into play was the initial use of Web Services. I had response time metrics on every single web service request in the system. This became valuable for many reasons. First, because the thing collecting the new metrics was new infrastructure, everyone wanted to blame it when something went wrong. The metrics it collected easily showed that it wasn’t the source of any problem, and actually was a great tool in narrowing where possible problems were. The frustration switched more to the systems that didn’t have these metrics available because they were big, black boxes. Secondly, we caught some rogue systems. A service that typically had 200,000 requests per day showed up on Monday with over 3 million. It turns out a debugging tool had been written by a project team, but that tool itself had a bug and started flooding the system with requests. Nothing broke, but had we not had these metrics and someone looking at them, it eventually would have caused problems. This could have went undetected for weeks. Third, we saw trends. I looked for anything that was out of the norm, regardless of whether any user complained or any failures occurred. When the response time for a service had doubled over the course of two weeks, I asked questions because that shouldn’t happen. This exposed a memory leak that was fixed. When loads that had been stable for months started going up consistently for two weeks, I asked questions. A new marketing effort had been announced, resulting in increased activity for one service consumer. This marketing activity would have eventually resulted in loads that could have caused problems a couple months down the road, but we detected it early. An unintended consequence was a service that showed a 95% failure rate, yet no one was complaining. It turns out a SOAP fault was being used for a non-exceptional situation at the request of the consumer. The consuming app handled it fine, but the data said otherwise. Again, no problems in the system, but it did expose incorrect use of SOAP.

While these metrics may not all be pertinent to the EA, you really only know by looking at them. I’d much rather have an environment where metrics are universally available and the individuals can tailor the reporting and views to information they find pertinent. Humans are good at drawing correlations and detecting anomalies, but you need the data to do so. The collection of these metrics did not have any impact on the overall performance of the system, however, they were architected to ensure that. Metric collection should be performed as an out-of-band operation. As far the practice of EA is concerned, one metric that I’ve seen recommended is watching policy adherence and exception requests. If your rate of exception requests is not going down, you’re probably sitting off in an ivory tower somewhere. Exceptions requests shouldn’t be at zero, either, however, because then no one is pushing the envelope. Strategic change shouldn’t solely come from EA as sometimes the people in the trenches have more visibility into niche areas for improvement. Policy adherence is also needed to determine what policies are important. If there are policies out there that never even come up in a solution review, are they even needed?

The biggest risk I see with extensive instrumentation is not resource consumption. Architecting an instrumentation solution is not terribly difficult. The real risk is in not provided good analytics and reporting capabilities. It’s great to have the data, but if someone has to perform extracts to Excel or write their own SQL and graphing utilities, they can waste a lot of time that should be spent on other things. While access to the raw data lets you do any kind of analysis that you’d like, it can be a time-consuming exercise. It only gets worse when you show it to someone else, and they ask whether you can add this or that.

EDA begins with events

EDA begins with events

Joe McKendrick asks, “Is EDA the ‘new’ SOA?” First, I’ll agree with Brenda Michelson that EDA is an architecture that can effectively work in conjunction with SOA. While others out there view EDA as part of SOA, I think a better way of viewing it would be that services and events must both be part of your technology architecture.

The point I really want to make however, which expounds on my previous post, is that I simply think event-oriented thinking is the exception, rather than the norm for most businesses. I’m not speaking about events in the technical sense, but rather, in the business sense. What businesses are truly event driven, requiring rapid response to change? Certainly, the airlines do, as evidenced by JetBlue’s recent difficulties. There are some financial trading sectors that must operate in real-time, as well. What about your average retail-focused company, however? Retail thinking seems to be all about service-based thinking. While you may do some cold calls, largely, sales happen when someone walks into the store, goes to the website, or calls on the phone. It’s a service-based approach. They ask, you sell. What are the events that should be monitored that would trigger a change in the business? For companies that are not inherently event-driven, the appropriate use of events are for collecting information and spotting trends. Online shopping can be far more informative for a company than brick-and-mortar shopping because you’ve got the clickstream trail. Even if I don’t buy something, the company knows what I entered in the search box, and what products I looked at. If I walk into Home Depot and don’t purchase anything, is there any record of why I came into the store that day?

Again, how do we begin to go down the direction of EDA? Let’s look at an event-driven system. The October 2006 issue of Business 2.0 had a feature on Steve Sanghi, CEO of Microchip Technology. The article describes how he turned around Microchip by focusing on commodity processors. As an example, the articles states that Intel’s automotive-chip division was pushing for “a single microprocessor near the engine block to control the vehicle’s subsystems and accessories.” Microchip’s approach was “to sprinkle simpler, cheaper, lower-power chips throughout the vehicle.” Guess what, today’s cars have about 30 micro-controllers.

So, what this says is that the appropriate event-based architecture is to have many, smaller points of control that can emit information about the overall system. This is the way that many systems management products work today- think SNMP. To be appropriate for the business, however, this approach needs to be generating events at the business level. Look at the applications in your enterprise’s portfolio and see how many of them actually publish any sort of data on how it is being used, even if it’s not in real time. We need to begin instrumenting our systems and exposing this information for other purposes. Most applications are like the checkout counter at Home Depot. If I buy something, it records it. If I don’t buy something and just exit the store, what valuable information has been missed that could improve things the next time I visit?

I’d love to see events become more mainstream, and I fully believe it will happen. I certainly won’t argue that event-driven systems can be more loosely coupled, however, I’ll also add that the events we’re talking about then are not necessarily the same thing as business events. Many of those things will never be exposed outside of IT, nor should they be. It’s the proper application of business events that will drive companies opening up their wallets to purchase new infrastructure built around that concept.

IT Conversations Podcast

IT Conversations Podcast

Ed Vazquez and I were invited to join Phil Windley and Scott Lemon on Phil’s Technometria series within IT Conversations for a discussion on SOA, with quite a bit of detail on SOA Governance. Give it a listen and feel free to follow up with any questions.

You can download the podcast here.

The human side of SOA/BPM

The human side of SOA/BPM

Two recent posts that were completely unrelated have prompted me to write a little bit about the human interaction side of SOA and BPM. First, in response to the debate on maturity levels between myself and David Linthicum, Lori MacVittie posted this entry on the F5 DevCentral blogs. She didn’t get into the debate on maturity levels, but rather brought up a point about the use of the term orchestration. She states:

Orchestration of applications is a high level automation mechanism that can’t really be completed until there is a solid underlying SOA infrastructure and set of common services in place. It’s the pinnacle of SOA achievement, the ultimate proof that an organization SOA can indeed provide the benefits touted by pundits. But orchestration of services should also be the mechanism by which applications are constructed.

The second post that caught my eye was Ismael Ghalimi’s post, “What is Wrong with BPM.” In this post, he talks about the problems customers face in selecting a BPM product and some of the things that customers run into after the purchase has been made and they try leveraging the solution on one of their real business problems. He states:

Then comes the really fun part: the business folks want a different user interface for their workflow. The one you got out of the box seems to be working pretty well, and you could display your company logo at the top left, but somehow the suits have something different in mind, and they want it now. They paid $300,000 for some magic pixie dust that gives them business agility, and they expect it to make you a contortionist worthy of a full-time job with Cirque du Soleil. So you end up spending the next six months writing massive amounts of JavaScript code that will hardcode the customer’s process deep into the user interface. You will be late, over budget, and won’t benefit from future software upgrades, for what you have now is built upon a completely different codebase. Great…

The two things I want to call out are Lori’s phrase “orchestration of applications” and Ismael’s laments about the quality of the user interface. I believe both of these posts are hitting on an element that is frequently forgotten around SOA, which is the human interaction. Regardless of how many services you build, some user is still going to need a front end, and there are inherently different concerns involved. Ismael’s absolutely right that some bare bones web form creation tool slapped onto the ugly schemas that represent the process context just don’t cut it. While 5-10 years ago, you may have been able to limp by with basic HTML forms, today’s web UIs involve AJAX, CSS, JavaScript, Flash, and much more. The tools that are calling themselves orchestration engines excel at what Lori calls orchestration of services (the BPEL space), but I don’t know that there are many that are really excelling at business process orchestration. I’m using my definition of business process orchestration here, which is both the human activities and the automated activities. I’m guessing that this is what Lori meant by orchestration of applications, however, I try not to use the term application anymore. It implies a monolithic approach where everything is owned end-to-end, and that simply won’t be the case in the future. If I do use the term, it’s reserved for the human facing component of the technology solution.

True business process orchestration that includes the human element, is not one that we’re seeing a lot of case studies on, but it’s where we need to set our sights. The problem is quite difficult, as the key factor is context. When I was working with a team on a reference solution architecture for BPM technology, one of the challenges was how and when to bring in context. If you rely on events to trigger state transitions, should those events carry references to information, or the contextual information itself? If it contains references, then you need access to all of the associated information stores, and you need to figure out what information is relevant for the problem at hand. It’s hard enough to get this right for an automated system where the information required is probably well defined. Now try getting it right when the events are tied back to a user interface. The problem is that every scenario may require a different set of information. As humans, we’re good at determining correlations and understanding where to go. Systems are not. Our goal should be to creating solutions that support the flexible context required for true business process orchestration. I think this will keep many of us gainfully employed for years to come.

The Scope of SOA Adoption

The Scope of SOA Adoption

I just finished giving a webinar on the importance of SOA pilots with Alex Rosen, and I hope the attendees found it informative. One of the things that I discussed in the webinar was the scope of SOA adoption. Given the recent attention to my last post, I thought I’d discuss it a bit more, since it’s one of the two dimensions of the maturity matrix. It’s also what makes the effort more than just a “search and replace” on the SEI CMMI models as one commenter over on InfoWorld thought.

The last post introduced the levels of maturity, which are:

- Ad Hoc

- Common Goals

- Pilot

- Extend

- Standardize

- Optimize

Those levels are a pretty straightforward way of describing the maturation process of just about anything. So what’s really import is the other dimension which defines exactly what we’re maturing.

In the case of this model, we’re discussing SOA adoption maturity. SOA adoption is not simply about purchasing technology. No one can sell you an SOA, although there was someone selling “SOA in a box” back around Christmas on eBay in Australia. SOA adoption does involve new technologies that can provide support in service development and hosting, such as orchestration engines or web service frameworks, service connectivity, such as SOA appliances or ESBs, and service management. SOA adoption also involves organizational changes. If your organization is structured around application development, which team is responsible for building a service that spans multiple groups? SOA adoption involves governance, whether it be funding models, design time policies, or run time policies. SOA adoption involves new processes designed around the consumer/provider interaction. SOA adoption involves training and communication. How do we market services that have been created to ensure their reuse? Clearly, SOA adoption involves architecture. Enterprise architecture must provide appropriate reference architectures and reviews to ensure both tactical and strategic success. SOA adoption involves Operational Management. Services can’t be dumped into production and forgotten, we must take a proactive approach to monitoring and metric collection and feed that information back into the machine for continuous improvement.

SOA is not easy. If it were, we’d all be done by now. Every company will have different drivers, and different technology needs. An assessment of their maturity in SOA adoption should examine all of dimensions required.

SOA Maturity Model

SOA Maturity Model

David Linthicum recently re-posted his view on SOA maturity levels and I wanted to offer up an alternative view, as I’ve recently been digging into this subject for MomentumSI.

Interestingly, Dave calls out a common pattern that other models he’s seen define their levels around components and not degrees of maturity. He states:

While components are important, a maturity model is much more important, considering that products will change over time…

I completely agree on this. Maturity is not about what technologies you use, it’s about using them in the right way. Comparing this to our own maturity, just because you’re old enough to drive a car, doesn’t mean you’re mature. Just because you’ve purchased an ESB, built a web service, or deployed a registry doesn’t mean you’re mature.

Dave then presents his levels. I’ve cut and paste the first sentence that describes each level here.

- Level 0 SOAs are SOAs that simply send SOAP messages from system to system.

- Level 1 SOAs are SOAs that also leverage everything in Level 0 but add the notion of a messaging/queuing system.

- Level 2 SOAs are SOAs that leverage everything in Level 1, and add the element of transformation and routing.

- Level 3 SOAs are SOAs that leverage everything in Level 2, adding a common directory service.

- Level 4 SOAs are SOAs that leverage everything in Level 3, adding the notion of brokering and managing true services.

- Level 5 SOAs are SOAs that leverage everything in Level 4, adding the notion of orchestration.

While these levels may be an accurate portrayal of how many organizations leverage technology over time, I don’t see how they are an indicator of maturity, because there’s nothing that deals with the ability of the organization to leverage these things properly. Furthermore, not all organizations may proceed through these levels in the order presented by Dave. The easiest one to call out is level 5: orchestration. Many organizations that are trying to automate processes are leveraging orchestration engines. They may not have a common directory yet, they may have no need for content based routing, and they may not have a service management platform. You could certainly argue that they should have these things in place before leveraging orchestration, but the fact is, there are many paths that lead to technology adoption, and you can’t point to any particular path and say that is the only “right” way.

The first difference between my efforts on the MomentumSI model and Dave’s levels is that my view is targeted around SOA adoption. Dave’s model is a SOA Maturity Model, and there is a difference between that and a SOA Adoption Maturity Model. That being said, I think SOA adoption is the right area to be assessing maturity. To get some ideas, I first looked to other areas, such as CMMI and COBIT. If we look at just the names of the CMMI and COBIT levels, we have the following:

| Level | CMMI | COBIT |

| 0 | Non-Existent | |

| 1 | Initial | Initial |

| 2 | Managed | Repeatable |

| 3 | Defined | Defined |

| 4 | Quantitatively Managed | Managed |

| 5 | Optimizing | Optimized |

So how does this apply to SOA adoption? Quite well, actually. COBIT defines a level 0, and labels it as “non-existent.” When applied to SOA adoption, what we’re saying is that there is no enterprise commitment to SOA. There may be projects out there building services, but the entire effort is ad hoc. At level 1, both CMMI and COBIT label it as “Initial.” Again, applied to SOA adoption this means that the organization is in the planning stage. They are learning what SOA is and establishing goals for the enterprise. Simply put, they need to document an answer to the question “Why SOA?” At level 2, CMMI uses “Managed” and COBIT uses “Repeatable.” At this level, I’m going to side with CMMI. Once goals have been established, you need to start the journey. The focus here is on your pilot efforts. Pilots have tight controls to ensure their success. Level 3 is labeled as “Defined” by both CMMI and COBIT. When viewed from an SOA adoption effort, it means that the processes associated with SOA, whether it be the interactions required, or choosing which technologies to use where, have been documented and the effort is now underway to extend this to a broader audience. Level 4 is labeled as “Quantitatively Managed” by CMMI and “Managed” by COBIT. If you dig into the description on both of these, what you’ll find is that Level 4 is where the desired behavior is innate. You don’t need to handhold everyone to get things to come out the way you like. Standards and processes have been put in place, and people adhere to them. Level 5, as labeled by CMMI and COBIT is all about optimization. The truly mature organizations don’t set the processes, put them in place, and then go on to something else. They recognize that things change over time, and are constantly monitoring, managing, and improving. So, in summary, the maturity levels I see for SOA Adoption are:

- Ad hoc: People are doing whatever they want, no enterprise commitment.

- Common goals: Commitment has been established, goals have been set.

- Pilot: Initial efforts are underway with tight controls to ensure success.

- Extend: Broaden the efforts to the enterprise. As the effort expands beyond the tightly controlled pilots, methodology and governance become even more critical.

- Standardize: Processes are innate, the organization can now be considered a service-oriented enterprise.

- Optimize: Continued improvement of all aspects of SOA.

You’ll note that there’s no mention of technologies anyway in there. That’s because technology is just one aspect of it. Other aspects include your organization, governance, operational management, communications, training, and enterprise architecture. SOA adoption is a multi-dimensional effort, and it’s important to recognize that from the beginning. I find that the maturity model is a great way of assessing where an organization is, as well as providing a framework for measuring continued growth. That being said, your ability to assess it is only as good as your model.

Integration, not convergence

Integration, not convergence

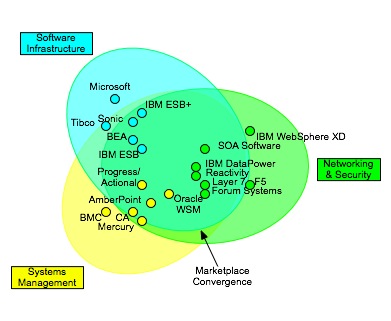

I recently had the opportunity to discuss the positioning of SOA appliances and it caused me to revisit my convergence model, as shown here:

This diagram was intended to show the challenges that enterprise face in choosing vendors today, as there are solutions from multiple product spaces. The capabilities frequently associated with activities “in the middle” can come from network appliances, application servers, ESBs, service management systems, etc. My original post talked about the challenges that organizations face in trying to pick a solution. A key factor that must be weighed is the roles in the organization. My view is that the activities in the middle should beconfigured, not coded. That’s a topic for another post, however.

I started thinking about the future state, and realized that while the offerings from vendors overlap today, that shouldn’t be the long term trend. Even vendors that can cover the entire space do it with multiple products. The right model that we should be shooting for is one that looks like this:

In this model, we have four distinct components. Service hosting is concerned with the development and execution of services. Service connectivity consists of the capabilities in the middle: routing, mediation, etc. Service management provides management facilities over both of these domains. All of these systems rely on a set of information resources which provide both the information to process, as well as the policy and meta-information required for the appropriate execution of the systems. A registry/repository, therefore, would fall into the information resource domain.

What we’d like is for all of these domains to be integrated in an open, standards-based manner. Unfortunately, we’re still a ways off from that day. There have been some proprietary efforts to create integrated solutions that look like this, such as the Governance Interoperability Framework effort by Systinet, but there’s still a long way to go. None of the vendors associated with GIF are the big players in the service hosting space (IBM, BEA, Oracle, Microsoft, etc.), and the integration standards are not open. When we have open, integration standards, we can now begin to create the feedback loop.

One short-term issue that needs to improve is the tight coupling of management consoles to the platforms. In the model, service management is loosely coupled. It integrates with the other domains through loosely coupled services, all of the best practices of SOA. Today, service hosting platforms and service connectivity systems all come with their own management consoles. In order to enable this model, the management architecture of those systems must be built on SOA principles. That means that all of the capabilities that can be managed should be exposed as services. You want to deploy a new application to the application server? Call the application deployment service. This creates a great situation for automated build systems. Out of the box, the build process could be executed in your favorite BPEL engine, with controls for compilation, automated testing, source code tagging, and deployment all orchestrated through web service interactions. Now add in a feedback loop by which metrics cause additional provisioning, or even where an uncaught exception results in a tag being placed on the source files associated with the stack trace to aid in debugging. It all begins with having the services available. Ask your vendors one simple question: are all the capabilities available through the management console also available as services?

An answer to slum control

An answer to slum control

Vilas posted a response to some of the postings (here and here) I made regarding the relationship of city planning to EA/SOA. He provides an example of a business sponsor that promotes a program that can add million dollars to the bottom line, but has an extremely short timeline, one that requires the existing architectural guidelines, principles, and processes to be short-circuited, or more likely, completely ignored. He compares this effort to a slum getting developed in a nice city.

I’m not going to argue that this situation doesn’t happen. It does. What I will argue, however, is that the fact that it allowed to be built can be a case of ineffective governance. The governance policies and processes have to be about encouraging the desired behavior. If the policies and processes aren’t consistent with the desired behavior, it’s a case of bad governance. In this example, this is likely a rapid growth opportunity. If the enterprise as a whole is in a cost cutting mode, I have a hard time believing that this rapid growth scenario would pass the governance checks and be viewed as a “solid business case.” If the corporate leaders have decided that the best direction for the company is to cut costs, odds are that a project such as this will never make it out of the governance process to begin with. If the company is focused on increasing revenue and growth, odds are it has taken more of a federated governance model, and allows individual business units to make decisions that are in their own best interest, sometime introducing redundant technology in order to meet the schedule demands of the growth cycles. If the enterprise architects in this model are instituting technical governance that constrains that growth, again, they’re acting in a way that is inconsistent with the goals of the organization, a case of bad governance. In either case, that mismatch will eventually cause problems for the organization. In the case of city, it may bring in crime, lower property values, and cause prosperous businesses and their revenues to move elsewhere. In the business world, it could cause a lack of focus on core capabilities, cost overruns, and fragmentation within. None of these risks were probably included in the business plan.

This is the dilemma of the enterprise architect or really anyone with some authority in the governance process. Growth is usually something that is important and achievable in the short term, but difficult to sustain in the long term. Growth has to occur in other areas, while cost cutting measures must be introduced in the former areas. Cost cutting leading to the elimination of redundancy, and if the technology wasn’t planned for that eventual occurrence from the beginning, the effort to reduce costs may eat away any potential savings. This is where the service abstraction is extremely important. Correctly placed services can position a company to consolidate where appropriate down the road. It will pay benefits when a merger and acquisition must occur by providing an analysis point (the service portfolio) from both a business and technology perspective to better estimate the cost of the integration activities.

Upcoming Webinar on SOA Pilots

Upcoming Webinar on SOA Pilots

Alex Rosen and I will be giving a webinar next Friday on the role of pilots in achieving SOA success. I haven’t blogged on SOA Pilots in quite some time (March 23rd of last year, to be exact). It’s always interesting to go back and read some of my past posts to see how my thinking has evolved. I had quoted the ZapThink guys, as well as Miko Matsumura in that entry, stating:

Miko stated that the only ones getting it right were ZapThink, who state that “the things you do in a pilot are the exact opposite of what you need to do to get to enterprise scale.” For the record, I agree. This all comes down to defining the pilot properly. In their book, “Service Orient or Be Doomed!” Jason and Ron call out three SOA Pilot essentials: an architectural plan (the pilot will cover some portion of it), a specific scope, and clear acceptance criteria.

There shouldn’t be much controversy over these, but yet, the case studies and whitepapers that I see presented don’t have these elements, and it’s usually because the study is equating web services usage with SOA. Taking a user-facing customer portal and extending it by allowing customers to integrate their systems directly can be a good thing, but is it really an SOA pilot?

I went on in the entry to lock in on the subject of culture change, stating: “a proper SOA pilot is to pick a problem that will require the organization to see the cultural changes that are necessary to become a service provider.” I still think that this is the case, however, I would also say that I was being just as narrow as the teams that strictly focus on using Web Services for the first time.

What you’ll find in the webinar is that SOA adoption involves many dimensions. One of those dimensions is technology based. Another dimension is cultural. I’ve been working with my colleagues on a maturity model that outlines these dimensions and the stages that an organization goes through across all of them. Pilot efforts should cover all of these. It may be done in one large program, or there may be several pilot projects. Every organization is different, therefore, there is not a one size fits all project that every organization should embrace.

If this sounds interesting to you, then I encourage you to sign up here, and listen in on Friday the 16th, at 1pm Eastern Time (Noon central, 10AM Pacific).

Your next task on the apprentice…

Your next task on the apprentice…

I want to turn on Donald Trump next Sunday night and see him task the teams with the successful creation and marketing of SOA within an enterprise. Okay, so it can’t be done within the day or two that they normally have, and outside of some Dilbert-esque quotes, it probably wouldn’t make for good TV. What it would do, however, is allow IT to see what their culture needs to be like in the future.

There’s a discussion just getting started in the Yahoo SOA group that raises some questions about the importance of marketing in SOA. A frequent complaint in the boardroom on “The Apprentice” is that the marketing strategy didn’t cut it and as a result, the person responsible for marketing on that task is fired. IT isn’t made up of bunch of people with MBA’s from Harvard, Wharton, or even Trump University. I have two degrees from the College of Engineering at the University of Illinois. During my stay there, I was not required to take any marketing courses, although the Computer Science department did require students in their undergraduate engineering program to take 4 courses outside of the department (independent of other electives) to which CS could be applied. The most popular area was business, with my choice, psychology, being second. The typical techie does not have formal training in marketing or other aspects of running a business, so it’s no surprise that we have a hard time with it.

We need to bring some business savvy into the IT department. I’m not talking about an understanding of the business being supported by IT (although that’s important too), I’m talking an understanding of how to succeed in business. Marketing, sales, product development, research, etc. A service provider needs to think of themselves as a vendor. They need to have a customer centric focus, with an understanding of the market trends (i.e. the business goals), customer needs, product lifecycles, resource availability, etc. to be successful. IT cannot simply be order takers in the process, because technology usage within an enterprise is not a commodity. The business side can’t simply go to IT Depot at the nearest shopping zone and pick up what they need. There are elements of technology that can be, and this will continue to fuel SaaS and other managed services, but here and now, the need for the IT department still exists. It’s time to change the IT culture, and get the development teams thinking about Service Management and a more business-like approach to their efforts.

Update: While the whole idea of bringing MBAs in was somewhat in jest, this is exactly what IBM did. Joe McKendrick’s eBizQ SOA in Action blog brought it to my attention, here’s a link to the original eBizQ story.

Rogue IT and governance

Rogue IT and governance

Recently, there’s been a few posts that have discussed the role of the individual in an SOA effort. David Margulius of InfoWorld posted an article about a doctor that took it into his own hands to create an electronic records system for outpatient services. Joe McKendrick of ZDNet and eBizQ followed on with some commentary. Prior to this, there was an article by a developer that was particularly critical of Enterprise Architecture.

Both of these articles raise some interesting points, and for the discussion, we need to go back to the city planning analogy that I recently discussed. If we were to equate these two technology related activities back to the city planning analogy, what would we have? In the case of the doctor that built his own electronic outpatient records system, let’s look at a recycling program. It’s entirely possibly that a homeowner’s organization could use some of the dues collected and implement a recycling program for an individual subdivision. It’s even possible for an individual homeowner to take their recycling to some provider elsewhere. Does it work? Absolutely. Is it cost-effective at the city level? Well, maybe not. Every individual getting in their car and driving to the nearest recycling center will be more expensive than a few trucks coming from the center for curbside pickup. The homeowners organization may be slightly more cost effective, but if each subdivision picks their own provider, you could have problems with far more recycling trucks on the street than are really necessary. The real concern, however, comes back to the problems in the first place. Why didn’t the city council put a recycling program in place? The fact that the city failed to act on this in a timely manner for its citizens is what causes a homeowner or homeowner’s organization to take matters into their own hands.

Likewise, let’s take the case of the frustrated developer. Here, the author called out:

Projects are driven by business deadlines, and not by the time it will take to get things right. So the foundation starts out weak…

This sounds like a case of being doomed from the start. In the city planning analogy, there are many scenarios, ranging from fixing a pothole in a street, to building highway interchanges. How many stories have been there about some worker that follows the letter to the T? They’re told to fix a pothole, so they fix that pothole, and only that pothole, regardless of whether or not the street looks like the surface of a golf ball. Some major development project is put under way, and winds up having huge cost overruns because an over-aggressive schedule.

While some may think that the core of the problem is too much governance, it’s not. The problem is ineffective governance. There needs to be an understanding from top to bottom of the roles and responsibilities associated with decision making and all need to be held accountable. A developer that isn’t following the guidelines isn’t a good thing, nor is an architect that establishes the wrong guidelines. An enterprise architect that obsesses about particular lines of code in a project is focused on the wrong thing. The city council shouldn’t be mandating what color a homeowner paints their bathroom. At the same time, there will always be gaps, and there will always be people with time on their hands to address them, like the doctor in the InfoWorld article. A key to being successful is the creation of the appropriate framework so those people can fill those gaps, but in a way that leads not only to short term success, but long term success, as well. I’m just as guilty as anyone else of jury-rigging a solution for a problem that I had, and then telling a few people about it, who in turn told their friends about it, etc. and the time I spent on it starting going up and up. The problem was a lack of understanding of either the need or the value that would achieved from the solution.

SOA is just another example of this. I recently had a discussion with Phil Windley about an upcoming article. In our discussion, one of the things I mentioned was that I felt that the technology governance (i.e. EA) needs to get in sync with the traditional IT governance (i.e., project scoping and funding). Project establish boundaries, and if those boundaries make it difficult to build services that have broader benefit, the odds are already stacked against you. We need to find a way to have those services be built the right way, and that may be more about changing the way that IT operates than it is about using a particular technology.

In short, the groups that comprise IT Governance in my opinion, EA and Management, need to establish the right guidelines and the right funding models for SOA, and really IT as a whole, to be successful. For some larger efforts, it will involve significant planning and effort from those areas. The smaller efforts will still occur, however, and they can’t be ignored either. An environment that encourages the individual to contribute to the overall success, and helps them to contribute in a constructive, rather than destructive way, will be the most successful. Sometimes it is necessary to deny a building permit for the greater good. The best situations, however, are where it can be turned into a win-win situation for both.

EA Consulting

EA Consulting

James McGovern posted a question for me to answer:

“…crisply define the distinction between consulting firms who offer services that are consumed by enterprise architecture teams vs. the actual act of practicing enterprise architecture?”

In thinking about this, my first thoughts were pretty simplistic. Unless the consultant is in a long-term staff augmentation role, the consultant assists, the corporate EA does. That’s painfully obvious, however, and I don’t think it’s what James was really asking about. As I thought about this, it really came back to collaboration. In order for a consulting firm to be successful in the long term, it has to leverage the breadth of exposure it has. Within an enterprise, the opportunities for cultural breadth (corporate culture) are minimal. It may happen when a change in management is made, or when a merger or acquisition occurs, but in general, you settle into one way of doing things. A consulting firm, on the other hand, gets exposure to many corporate cultures, and has to find a way to make an organization successful within that culture, potentially being an agent for change. An 8 week or 12 week assignment is typically not long enough to introduce significant cultural change, however.

Given that the consulting firm has the breadth of exposure, it is critical that the consulting firm collaborate on engagements so that the best solutions can be offered. Even if I’m the only person assigned to a particular engagement, I will bounce ideas off of my peers to get their thoughts. By seeing what different organizations do, and understanding which approaches work best with a particular corporate culture, the engagements are much more likely to be successful.

Within an enterprise, I don’t think the notion of collaboration is as important as it should be. All too often, it’s about turf battles and clear lines of responsibility. When I ask my teammates a question, I don’t have any fear that they’re going to get recognition by my boss before I do. I ask them because I want the best solution for my client. In the enterprise world, internal advancement and recognition is on the mind of many individuals, and may come at the expense of creating a collaborative, team approach.

All of this is not specific to enterprise architecture, but I think it’s even more important at this level. In my experience as part of an EA team prior to becoming an enterprise, it became very clear that architecture couldn’t be done in a vacuum. Yet, the corporate culture makes it very difficult to foster the type of collaboration that was needed to make it successful. Too many meetings, too many fire drills, and too many time-dependent activities (i.e. top priority is some date in a project plan, not necessarily getting the best answer). This isn’t a knock on my former employer, it’s probably true of most enterprises. Enterprise architecture, by its very nature, requires collaboration. The EA focused on Security has to be working closely with the EA focused on Information and the EA focused on networking technologies, etc. Ironically, what often causes that collaboration to occur quickly? Bringing in a consultant. The consultant needs to quickly understand where an organization is, and it meets bringing all of the right people together and having the right discussions.