Archive for the ‘IT’ Category

More on ITIL and SOA

More on ITIL and SOA

In his “links” post, James McGovern was nice enough to call additional attention to my recent ITIL and SOA post, but as usual, James challenged me to add additional value. Here’s what he had to say:

Todd Biske provides insight into how ITIL can benefit SOA but misses an opportunity to provide even more value. While it is somewhat cliche to talk about continual process improvement, it would be highly valuable to outline what types of feedback do operations types observe that could benefit the software development side of the house.

I thought about this, and it actually came down to one word: measurement. You can’t improve what you’re not measuring. It’s debatable as to whether or not operations does any better than software development in measuring the service they provide, but operations is probably in a better position to do so. Why? There is less ambiguity about the service being provided. For example, a common service from operations in big IT shops is building servers. They can measure how many servers they’ve built, how quickly they’ve been built, and they and how correctly they’ve been built, among other things.

In the case of softwre development, is the service being provided software development, or is the capability provided by the software? I’d argue that most shops are focused on the former. If you measure the “software development” service, you’ll probably measure whether the effort was completed on time and on budget. If, instead, you measure based on the capability provided by the software, it now becomes about the business value being provided by the software, which, in my opinion, is the more important factor. Taking this latter view also positions the organization for future modifications to the solutions. If my focus is solely on time and budget, why wouldn’t I disband the team when the project is done? The team has no vested interest in adding additional value. They may be challenged on some other project to improve their delivery time or budget accuracy, but there’s no connection to business value. Putting it very simply, what good does it do to deliver an application on time and on budget that no one uses?

So, back to the question, what can we learn from the ops side of the world. If ops has drunk the ITIL kool-aid, then they should be measuring their service performance, the goals for it should be reflected in the individual goals of the operations team, and it should be something that allows for improvement over time. If the measurement falls into the “one-time” measurement category, like delivering on-time and on-budget, that should be a dead giveaway that you may be measuring the wrong thing, or not taking a service-based view on your efforts.

ITIL and SOA

ITIL and SOA

I’ve been involved in some discussions recently around the topic of ITIL Service Management. While I’m no ITIL expert, the little bit of information that I’ve gleaned from these discussions has shown me that there are strong parallels between SOA and ITIL Service Management.

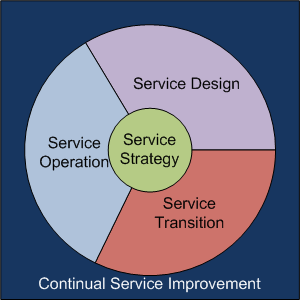

There’s the obvious connection that both ITIL Service Management and SOA contain the term “service,” but it goes much deeper than that (otherwise, this wouldn’t be worth posting). There are five major domains associated with ITIL: service strategy, service design, service transition, service operation, and continual service improvement. Here’s a picture that I’ve drawn that tries to represent them:

Keeping it very simple, service strategy is all about defining the services. In fact, there’s even a process within that domain called “Service Portfolio Management.” Service Design, Service Transition, and Service Operation are analogous to the tradition software development lifecycle (SDLC): service design is where the service gets defined, service transition is where the service is implemented, and service operation is where the service gets used. Continual Service Improvement is about watching all aspects of each of these domains and striving to improve it.

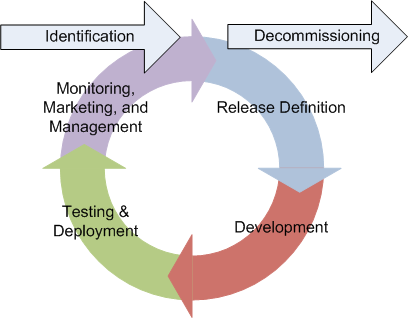

Now back to SOA side of the equation. I’ve previously posted on the change to the development process that is possible with SOA, most recently, this one. The essence of it is that SOA can shift the thinking from a traditional linear lifecycle that ends when a project goes live to a circular lifecycle that begins with identification of the service and ends with the decommissioning of the service. Instead, the lifecycle looks like this:

The steps of release definition, development, testing, and deployment are the normal SDLC activities, but added to this is what I call the triple-M activity: monitoring, marketing, and management. We need to do the normal “keep the lights on” activities associated with monitoring, but we also need to market the service and ensure its continued use over time, as well as manage its current use and ensure that it is delivering the intended business value. If improvements can be made through either improvements in delivery or by delivering additional functionality, the cycle begins again. This is analogous to the ITIL Service Management Continual Service Improvement processes. While not shown, clearly there is some strategic process that guides the identification and decommissioning activities associated with services, such as application portfolio management. Given this, these two processes have striking similarities.

What’s the point?

The message that I want you to take away is that we should be thinking about application and “web” service delivery in the same way that we are thinking about ITIL service delivery. Many people think ITIL is only about IT operations and the infrastructure, but that’s not the case. If you’re a developer, it equally applies to the applications that you are building and delivering. Think of them in terms of services and the business value that they deliver. When the project for version 1 ends, don’t stop thinking about it. Put in place appropriate metrics and reporting to ensure that it is delivering the intended value and watch it on a regular basis. Understand who your “users” are (it could be other systems and the people repsonsible for them), make sure they’re happy, and seek out new ones. Adopt a culture of continuous improvement, rather than simply focus on meeting the schedule and the budget and then waiting for the next project assignment.

Governance: Are you on the left or the right?

Governance: Are you on the left or the right?

Dan Foody of Progress Software posted a followup to my last post entitled, “Less Governance is Good Governance.” Clearly, when it comes to SOA governance, Dan falls on the right. For those of you not in the US, the right, when used in the political sense, refers to the Republican party. The Republican party is typically the champion of less government. On the opposite side of the political fence, over on the left, are the Democrats. The Democratic party is typically associated with big government and more regulation. This post isn’t about US politics, however, it’s about SOA governance.

In line with his right-facing view, Dan’s final statement in his post says, “As much governance as is absolutely necessary, but no more.” Well, the United States has had successful times when Congress at times when each party had the majority, likewise for the presidency. So, I don’t think that it’s a uniform truth that less governance is good governance. Good governance is not defined by how quickly your team comes to consensus, it’s defined on whether or not you achieve your desired behavior. Sometimes, that may only require a few policies. Other times, it may require lots of policies, and lots of regulation. It is completely dependent on the current behavior of your organization, the behavior you need to have to be successful, and the degree to which everyone in the organization understands it and agrees with it, which is why communication is so important. Left? Right? Both can be successful, it’s all about where you are and where you need to go.

Governance does not imply Command and Control

Governance does not imply Command and Control

In a recent discussion I had on SOA Governance with Brenda Michelson, program director for the SOA Consortium, she passed along a link to this article from Business Week. It’s the story of Tom Coughlin, coach of the Super Bowl champion New York Giants, and how he had to change from his reputation of an “autocratic tyrant” in order for the team to ultimately succeed.

What does this have to do with governance? When you think of governance, what comes to mind? My suspicion is that for most people, it’s not a positive image. At its extreme worst, I’ve heard many people describe governance as a slow, painful process that requires investing significant time preparing for a review by people who are out of touch with what a project is trying to do that ultimately results in the reviewers flaunting authority, the project team taking their lumps, and then everybody goes back to doing what they were doing with no real change in behavior other than increased animosity in the organization. In other words, exactly the situation that Tom Coughlin had with previous teams.

The fact is that governance is a required activity of any organization. Governance is the way in which an organization leverages people, policies, and processes to achieve a desired behavior. In the case of the New York Giants, their desired behavior was winning the Super Bowl. In years past, only people involved with setting the policies was the coaching staff, and the processes consisted of yelling and screaming. It didn’t work. When the desired behavior wasn’t achieved, change was needed, and that change was made in the governance. Players became involved in setting policies through a leadership council. That same council also became part of the governance process in both educating other players about the policies as well as ensuring compliance.

Unfortunately, when governance gets discussed, people naturally assume a command and control structure. When an individual sees a new statement “Thou shall do this” or “Thou shall not do that,” they think command and control, especially if they weren’t involved with the setting of the policy. As we grow, this sentiment becomes increasingly important. How many of us that live in large countries feel our politicians are disconnected from us, even if they are elected representatives? Those policies still need to be set, however, and there will always be a need for some form of authority to establish the policies. The key is how the “authority” is established and how they then communicate with the rest of the organization. If the authority is established by edict, and only consists of one-way communication (down) from the authority, guess what? You have a dictatorship with a command-and-control structure. If you set up representative groups, whether formal or informal, and focus on bi-directional communication, you can conquer that command-and-control mentality. The risk with that approach is that the need for “authority” is forgotten. Decisions still must be made and policies must be set, and if the group-think can’t do that, there will still be problems. Morale may not impacted in the same negative way as a command-and-control approach, but the end result is that you’re still not achieving the desired behavior.

Good governance is necessary for success, and open communication and collaboration is necessary for good governance. My recommendation is that if you are an in a position of authority (a policy setter and/or enforcer), you must keep the lines of communication open with your constituents and help them to set policies, change policies that are doing more harm than good, and understand the reasons behind policies. If you are a constituent, you need to participate in the process. If a policy is causing more harm than good in your opinion, make it known to the authorities. Sometimes that may result in a policy change. Sometimes it may result in you changing your expectations and seeing the reasons why compliance is necessary.

Cloud versus Grid

Cloud versus Grid

I am back from vacation and trying to catch up on my podcasts. In an IT Conversations Technometria Podcast, Phil Windley spoke with Rich Polski. Rich is working on Eucalyptus, an open source implementation of the Amazon EC2 interface.

Rich gave a great definition of the difference between grid computing and cloud computing. Grid computing typically involves a small number of users requesting big chunks of resources from a homogenous environment. Cloud computing typically involves a large number of users with relatively low resource requirements from a heterogenous environment.

Rich and Phil went on to discuss the opportunities for academic research in the cloud computing and virtualization spaces. If you are considering when and how to leverage these technologies, give it a listen.

Vacation

Vacation

No blogs for the next two weeks, most likely, unless I decide to post a picture from Colorado. We’re going on a two week family vacation. It will be a good break, as I’ve been spending a lot of time working on a book, and the first draft has just been completed. More on that to come! Thanks for reading, as always!

Information in the Enterprise

Information in the Enterprise

A thought occurred to me today as I was walking into work. Why is it that the first place I go, and probably most of my coworkers, when I want to find out something is the Google search box in my browser? Why don’t I use the search box on our corporate intranet?

There’s certainly no doubt that there’s a wealth of information out there on the internet. What’s interesting is that one of the reasons I started this blog back almost 3 years ago is I thought there were things I was encountering in my research for work that others might find valuable. It was probably about 6 months after I started blogging that someone at work did a Google search on something SOA or governance related, and up popped my blog in his results. It seems rather silly that a colleague at work had to go out to the public internet to find something that I had to say.

Being an Enterprise Architect, I create my fair share of Visio diagrams, PowerPoint presentations, and Word documents. In this day and age, there’s absolutely no reason that these things can’t be put into something like SharePoint and indexed so there are available via the search box on the intranet page. Unfortunately, not everything I do at work winds up in one of those documents, so I need to apply the same principles I used in creating this blog to what I do at work, and start making some of those discussions available internally, as well. What’s nice about internal blogs is they can be put into your RSS reader right along side external feeds. That won’t happen with search, unfortunately. This is actually one situation where I think it could be useful to have a company-specific version of the major browsers that would first direct searches in the default search box to the internal engine, and then follow that up with general search results from Google or somewhere else.

I encourage all of my readers who work in enterprises to think about how they can make more of their knowledge available to their co-workers through their intranets. If you don’t have internal support for blogging, wikis, and a decent search engine, it may be time to make the investment.

A Key Challenge of Context Driven Architecture

A Key Challenge of Context Driven Architecture

The idea of context-driven architecture, as coined by Gartner, has been bouncing around my head since the Gartner AADI and EA Summits I attended in June. It’s a catch phrase that basically means that we need to design our applications to take into account as much as possible of the context in which it is executed. It’s especially true for mobile applications, where the whole notion of location awareness has people thinking about new and exciting things, albeit more so in the consumer space than in the enterprise. While I expect to have a number of additional posts on this subject in the future, a recent discussion with a colleague on Data Warehousing inspired this post.

In the data warehousing/business intelligence space, there is certainly a maturity curve to how well an enterprise can leverage the technology. In its most basic form, there’s a clear separation between the OLTP world and the DW/BI world. OLTP handles the day to day stuff, some ETL (extract-transform-load) job gets run to put it into DW, and then some user leverages the BI tools to do analytics or run reports. These tools enable the user to look for trends, clusters, or other data mining type of activities. Now, think of a company like Amazon. Amazon incorporates these trends and clusters into the recommendations it makes for you when you log in. Does Amazon’s back-end run some sophisticated analytics process every time I log in? I’d be surprised if it did, since performing that data mining is an expensive operation. I’m guessing (and it is a guess, I have no idea on the technical details inside of Amazon) that the analytics go on in the background somewhere. If this is the case, then this means that the incorporation of the results of the analytical processing (not the actual analytics itself) is coded into the OLTP application that we use when we log in.

So what does this have to do with context-driven architecture? Well, what I realized is that it all comes down to figuring out what’s important. We can run a BI tool on the DW, get a visual representation, and quickly spot clusters, etc. Humans are good at that. How do you tell a machine to do that, though? We can’t just expect to hook our customer facing applications up to a DW and expect magic to happen. Odds are, we need to take the first step of having a real person look at the information, decide what is relevant or not with the assistance of analytical tools. Only then can we set up some regular jobs to execute those analytics and store the results somewhere that is easily accessible by an OLTP application. In other words, we need to do analysis to figure out what the “right” context is. Once we’ve established the correlation, now we can begin to leverage that context in a way that’s suitable for the typical OLTP application.

So, if you’re like me, and just starting to noodle on this notion, I’d first take a look at your maturity around your data warehousing and business intelligence tools. If you’re relatively mature in that space, that I expect that a leap toward context-driven applications probably won’t be a big stretch for you. If you’re relatively immature, you may want to focus on building that maturity up, rather than jumping into context-driven applications before you’re ready.

The Use of Incentives

The Use of Incentives

As usual, I had David Linthicum’s Real World SOA Podcast on during my drive into work today. I’m not going to pick on Dave today, however, as he was just the messenger. In fact, I liked that this week’s podcast mentioned the need for systemic change several times, which is a message that we need to continue to send out. See my last post for more on that subject. Anyway, Dave walked through this post from Joe McKendrick of ZDNet, entitled “Ten ways to tell it’s not SOA.” I hadn’t read this yet, but one item in particular stuck out when Dave mentioned it:

5) If developers and integrators are not being incented or persuaded to reuse services and interfaces, it’s not SOA. Without incentives or disincentives, they will keep building their own stuff.

The word in there that concerns me is “incented.” Many advocates for reuse also recommend some form of incentive program. Clearly, incentives are a possible tool to leverage for behavior change, but we’re much smarter than Pavlov’s dogs. Sometimes, people get too focused on the incentive, and not enough on the behavior. How many times do professional athletes put up big numbers in the last year of a contract because they’re “incented” by the free agent market in the upcoming off-season, only to then flop back down to their career .237 average after signing their multi-million dollar deal. Years ago, I was on a tiger team investigating what it would take to achieve reuse at our organization, and a co-worker would simply say, “Their incentive is that they get to keep their job.” Too often, incentives focus on one-time behaviors, rather than on changes that we want to become normal behavior.

As a very specific example on the risk associated with incentives, I’ve previously posted on how we need to provide context on the degree to which a service might be applicable in my horizontal and vertical thinking post. If you are a developer working in a “vertical” domain, the opportunity to write shared services simply doesn’t exist. Should that developer be penalized for not producing a reusable service? An incentive focused on writing shared services is meaningless for that developer. It’s like making a blanket statement to a baseball team that anyone who hits 20 home runs in a season will get an extra million dollars. You don’t want everyone swinging for the fences every at bat. Sometimes you need to lay down a sacrifice bunt. What about the pinch hitter who only get 100 at bats the whole season? Should they be unfairly penalized?

For me, there’s simply too a big of a risk of having incentives based on something that’s easy to quantify, rather than the actual desired behavior, and when applied to a broad audience, leaves some people out in the cold with no chance of getting the incentive through no fault of their own. Incentives are best used where a one-time change in behavior is needed due to extenuating circumstances, they should not be used to create behavior that should be the norm to begin with. As my colleague said, for normal behavior, your incentive is that you get to keep your job.

Governance and SOA Success

Governance and SOA Success

Michael Meehan, Editor-in-Chief of SearchSOA.com, posted a summary of a talk from Anne Thomas Manes of the Burton Group given at Burton’s Catalyst conference in late June. In it, Anne presented the findings of a survey that she did with colleague Chris Haddad on SOA adoption.

Michael stated:

Manes repeatedly returned to the issues of trust and culture. She placed the burden for creating that trust on the shoulders of the IT department. “You’re going to have to create some kind of culture shift,” she said. “And you know what? You’ve been breaking their hearts for so many years, it’s up to you to take the first step.”

I’m very glad that Anne used the term “culture shift,” because that’s exactly what it is. If there is no change in the way IT defines and builds solutions other than slapping a new technology on the same old stuff, we’re not going to even put a dent in the perceptions the rest of the organization has about IT, and are even at risk of making it worse.

The article went on to discuss Cigna Group Insurance and their success, after a previous failure. A new CIO emphasized the need for culture change, started with understanding the business. The speaker from Cigna, Chad Roberts, is quoted in Michael’s article as saying, “We had to be able to act and communicate like a business person.” He also said, “We stopped trying to build business cases for SOA, it wasn’t working. Instead use SOA to strengthen the existing business case.” I went back and re-read a previous post, that I thought made a similar point, but found that I wasn’t this clear. I think Chad nails it.

In a discussion about the article in the Yahoo SOA group, Anne followed up with a few additional nuggets of wisdom.

One thing I found really surprising was that the people from the

successful initiatives rarely talked about their infrastructure. I had

to explicitly solicit the information from them. From their

perspective, the technology was the least important aspect of their

initiative.

This is great to hear. While there are plenty of us out there that have stated again and again that SOA isn’t about applying WS-*/REST or buying an ESB, it still needs to be emphasized. A surprising comment, however, was this one:

They rarely talked about design-time governance — other

than improving their SDLC processes. They implemented governance via

better processes. Most of it was human-driven, although many use

repositories to manage artifacts and coordinate lifecycle. But again,

the governance effort was less important than the investment in social

capital.

I’m still committed to my assertion that governance is critical to a

successful SOA initiative–but only because governance is a means to

effect behavioral change. The true success factor is changing

behavior.

I think what we’re seeing here is the effects of governance becoming a marketing term. The telling statement is in Anne’s second paragraph- governance is a means to effect behavioral change. My definition of governance is the people, policies, and processes that an organization employs to achieve a desired behavior. It’s all about behavior change in my book. So, when the new Cigna CIO makes a mandate that IT will understand the business first and think about technology second, that’s a desired behavior. What are the policies that ensured this happened? I’m willing to bet that there were some significant changes to the way projects were initiated at Cigna as part of this. Were the policies that, if adhered to, would lead to a funded project documented and communicated? Did they educate first, and then only enforce where necessary? That sounds like governance to me, and guess what- it led to success!

Mentoring and Followup to Clarity of Purpose

Mentoring and Followup to Clarity of Purpose

James McGovern posted his own thoughts in response to my Clarity of Purpose post. In it, he asks a couple of questions of me.

“I wonder if Todd has observed that trust as a concept is fast declining.” I don’t know that I’d say it is declining, but I would definitely say that it is a key differentiator between well-functioning organizations and poorly functioning organizations. I think it’s natural that as an organization grows, you have to work harder to keep the trust in place. How many people in a small town say they trust their local government versus a big city, let alone the country? The same holds true for typical corporate IT. As James’ points out, trust gets eroded easily when things are over-promised and under-delivered. Specifically in the domain of enterprise architecture, we’re at particular risk because we often play the role of the salesperson, but the implementation is left to someone else. When things go bad, the customer directs their venom at the salesperson, rather than digging deep to understand root cause. We also too frequently look to point fingers rather than fix the problem. It’s unfortunate that too many organizations have a “heads must roll” approach which doesn’t allow people to make mistakes and learn. A single mistake is a learning opportunity. Making the same mistake over and over is a problem that must be dealt with.

“Maybe Todd can talk about his ideas around the importance of mentoring in a future blog entry as this is where EA collectively is weak and declining.” Personally, I think it’s a good practice to always have some amount of your enterprise architect’s time dedicated to project mentoring. Don’t assign them as a member of the project team where the project manager controls their tasks, rather, encourage them to actively work with the project team, keep up to date on what they are doing, and look for opportunities where you can help. The most important thing, however, is to have an attitude of contributing the help that is needed, rather than contributing your own wisdom. If you come in pontificating, going off on tangents, and expressing an “I know better” attitude, you’ll only get resentment. If, instead, you seek first to understand, as Stephen Covey suggests, you’ll have much better luck. While I was working as a consultant, I had a client who indicated that what they really needed was a mentor. For some consultants, this would have been perceived as the kiss of death, because it can result in an open-ended, warm body engagement, without clear expectations and deliverables. There’s a lot of risk when expectations aren’t clear and can change on a moment’s notice. In reality, the engagement was simply to listen and then offer suggestions and advice to either confirm what they already knew but lacked confidence to go after with conviction, or to suggest things that they might not have thought about. It’s not an easy task to do, but it is absolutely critical. I think an architect who is willing to stand by his or her strategy and see it through to completion, not necessarily from a hands-on perspective, but from a mentoring and guidance perspective, can build far more trust.

Clarity of Purpose

Clarity of Purpose

Do you have clarity of purpose in your job, your projects, your teams, your committees? I’m seeing more and more that lack of clarity in purpose is a very common problem, and one that frequently goes unnoticed until things are in a very bad state.

Why don’t we pick up on this? Human nature certainly has a part in this. We go through life being told what to do without being told why. Some things need to be done on trust- trust that the person giving the direction understands the purpose. If they don’t, then the problem can begin. Another problem is that I don’t believe we’re a community of Wallys. We like to be doing something, we like to be productive, and we like to have a purpose. Therefore, if we haven’t been given one, we’ll probably make one up. Unfortunately, in a team setting, my perception of purpose may differ from my teammates, which has the potential to create tension (there’s good tension and bad tension, but that’s a subject for another day). My teammate and I may have the same perception of purpose, but that may be different from someone outside of the team. That’s an even more dangerous situation, because now the team thinks they are doing good work, but the perception of an outsider is exactly the opposite.

Take my job: enterprise architecture. Most EA’s I know, myself included, would consider themselves big picture thinkers. Our purpose, however, is not just to establish strategic direction, but to ensure that strategic direction is followed. If all we do is create Visio and Powerpoint, and don’t also include planning, communication, and mentoring, are we success? All of the outsiders may talk to an enterprise architect and walk away thinking that person is brilliant and has a great vision, but if their purpose is also to get the organization there, and the organization isn’t moving any closer, that’s a problem.

Finally, I think it’s very easily to lose sight of our purpose as we get bogged down in the day to day efforts. It’s important to go back and review your purpose on a regular basis and make sure you’re staying on track and completing all aspects of it, and if not, seek help. Get a mentor or coach, recognize your strengths and weaknesses, and take the necessary steps to do it. If the current path isn’t working, something needs to change. If you don’t change, neither will the outcome.

FYI: I’ve signed up for Twitter. I’m somewhat skeptical about it, but I figured the only way of understanding whether its worth my time or not is to try it. My id is toddbiske, follow me here.

Comments on TUCON 2008 Podcast

Comments on TUCON 2008 Podcast

Dana Gardner moderated a panel discussion at Tibco’s User Conference (TUCON) on Service Performance Management and SOA. There were some great nuggets in this session, I encourage you to listen to the podcast or read the transcript. The panelists were Sandy Rogers of IDC, Joe McKendrick, Anthony Abbattista of Allstate, and Rourke McNamara of TIBCO.

First, Sandy Rogers of IDC commented that what she finds interesting “is that even if you have one service that you have deployed, you need to have as much information as possible around how it is being used and how the trending is happening regarding the up-tick in the consumption of the service across different applications, across different processes.” I couldn’t agree more on this item. I have seen first hand the value in collecting this information and making it available. Unfortunately, all too often, the need for this is missed when people are looking for funding. Funding is focused on building the service and getting it out the door on-time and on-budget, and operation concerns are left to classic up/down monitoring that never leaves the walls of IT operations. We need to adjust the culture so that monitoring of the usage is a key part of the project success. How can we make any statements on the value of a service, or any IT solution for that matter, if we aren’t monitoring how that service is being used? For example, I frequently see projects that are proposed to make some manual process more efficient. If that’s the value play, are we currently measuring the cost of the manual activity, and how are we quantifying the cost of doing it the new way? Looking at the end database probably isn’t good enough, because that only shows the end results of processing, not the pace of processing. Automated a process enables you to process more, but if demand is stable, the end result will still look the same. The difference lies in the fact that people (and systems) have more time available for other activities.

Sandy went on to state:

They (organizations) need a lot more visibility and an understanding of the strains that are happening on the system, and they need to really build up a level of trust. Once they can add on to the amount of individuals that have that visibility, that trust starts to develop, more reuse starts to happen, and it starts to take off.

Joe picked on this stating “that the foundation of SOA is trust.” No arguments here. If the culture of the organization is one of distrust, I see them of having very slim chances of having any success with SOA. Joe correctly called out that a lot of this hinges on governance. I personally believe that governance is how an organization changes behavior and culture. Lack of trust is a behavior and trust issue. Only by clearly stating what the desired behavior is and establishing policies that create that behavior can culture change happen.

Anthony provided a great anecdote from the roll-out of their ESB stating that they spent 18 months justifying its use and dealing with every outage starting with someone saying, “TIBCO is down.” In reality, it was usually some back end service or component being down, but since the TIBCO ESB was the new thing, everyone blamed it. By having great measurements and monitoring, they were able to get to root cause. I had the exact same situation at a prior company, and it was fun watching the shift as people blamed the new infrastructure, and I would say, “No, it’s up, and the metrics it has collected makes me think the problem is here.”

A bit later in the podcast, Joe mentioned a conversation with Rourke earlier in the day, commenting that “predictive analytics, which is a subset of business intelligence (BI), is now moving into the systems management space.” This sounds very familiar…

Rourke also made a great comment when referring to a customer who said “their biggest fear is that their SOA initiative will be a victim of its own success.” He went on to say:

That could make SOA a victim of its own success. They will have successfully sold the service, had it reused over and over and over and over again. But, then, because of that reuse, because they were successful in achieving the SOA dream, they now are going to suffer. All that business users will see from that is that “SOA is bad,” it makes my applications more fragile, it makes my applications slow down because so many people are using the same stuff.

That was a great point. SOA, if it is successful, should result in an increase in the number of dependencies associated with an IT solution. Many people shudder at that statement, but the important thing is that there should be those dependencies. What’s bad is when those dependencies aren’t effectively managed and monitored. The lack of effective management results in complicated, ad hoc processes that give the perceive that the technology landscape is overly complex.

This was one of the better panel discussion I’ve heard in a while. I encourage you to give it a listen.

Integration Competency Centers and SOA

Integration Competency Centers and SOA

Lorraine Lawson of IT Business Edge had a post last week that linked to my previous posts on Centers of Excellence and Competency Centers entitled, “The Best Practice That Companies Ignore.” In this article, she references an eBizQ survey that revealed that only 9% of respondents had a competency center or center of excellence. While she wasn’t surprised at this, she was surprised at recent comments from Ken Vollmer of Forrester that said the same is true for Integration Competency Centers, a concept that has been around for several years. In her discussion with Ken, she states he indicated that “any organization with mid-to-high-level integration issues could benefit from an ICC.” My take on the discussion was that Ken feels that every mid to large organization should have one (my opinion, neither he nor Lorraine stated this).

The real issue I had with some of the justifications for having an ICC was an underlying assumption that intergration is a specialized discipline. While this was the case 8-10 years ago, I think we’ve made significant progress. I actually think there is a specific detriment that an ICC can have to an SOA effort. When an ICC exists, integration is now someone else’s problem. I worry about my world, and I leave it up to the integration experts to make my world accessible to everyone else. It’s this type of thinking that will doom an SOA effort, because everyone’s first concern is themselves, not everyone else. To do SOA right, your service teams should be consumer-focused first.

Regarding ICCs, the reason I don’t think there is broad adoption of the concept is that majority of companies, even large enterprises, only have one or two major systems that represent 80% of the integration effort, typically either mainframe integration or ERP integration. Companies that have grown via acquisition may have a much more difficult problem with multiple mainframes, multiple ERP systems, etc., and for them, ICCs are a good fit. I just don’t think that’s 80% of the mid-to-large businesses.

The last piece of the message, and where she linked to my posts, deals with whether or not the ICC should temporary or not. Ken’s comment was that there are always new integration tools coming out, and the ICC should be responsible for them. I don’t agree with this. There are also new development tools coming out, and I don’t see companies with a development competency center. Someone does have to be responsible for integration technologies, but this could easily be part of the responsibilities for a middleware technology architect.

Applying the same argument to SOA, again, if it’s technology-focused, I don’t buy it. If we get into the space of SOA Advocacy and Adoption, then I think there’s some value. Clearly, individual projects building services does not constitute SOA. Given that, who is guiding the broader SOA effort? Perhaps what is ultimately needed is a SOA Advocacy Center or SOA Adoption Center that is repsonsible for seeing it forward. There’s no formula for this, though. A person dedicated to being the SOA Champion with excellent relationships in the organization could potentially do this on their own. Ultimately, this become just like any other strategic initiative. To acheive the strategy, the organization must put proper leadership in place. If it’s one person, great. If it’s a standing committee, great. Just as long as it is positioned for success. Putting one person in charge who lacks the relationships won’t cut it, but putting a committee together to establish those relationships will. Whether it’s permanent or not is dependent on whether the activities can become standard practice, or if there is a continual need for leadership, guidance, and governance.

Redefining Banking…

Redefining Banking…

Here’s an idea for some entrepreneur to go and run with, or even better, for someone to read and go, “That’s already been done! Go visit -blank-.” I was thinking about banking, budgets, and money management and was thinking just how inconvenient it is to move money around between various accounts. I’ve been a Quicken user for over a decade now, and it’s frustrating that there are still financial institutions that don’t download into Quicken easily. The second thing that occurred to me is that it still seems to difficult to move money around between different accounts. The average person can have a checking account, a saving account, a retirement account, an investment account (which may also require having accounts with each company that manages a mutual fund in that account), plus accounts for their family, credit cards, etc.

I thought back to when I was growing up and remember my Mom having a collection of envelopes at her desk, each of them containing the cash for the month for a particular category. This was how she created her budget. I also found out later about some of the other tricks my parents used for handling things like Christmas and vacations. They had additional bank accounts that were reserved for these expenses that were going to be larger and thus required a longer time period of savings. They’d rather get interest on it from a bank somewhere than keep it in an envelope on the desk.

Then it clicked. Why can’t a financial institution today provide an electronic equivalent of the envelopes my Mom used years ago? All the pieces should be there. We leverage electronic fund transfers every day, there’s absolutely no reason that this can’t be made more consumer friendly so that performing a transfer from my checking account into a custodial investment account for my kids is as simple as doing a “Transfer Funds” operation in Quicken. Does anyone make this easy today? I know there’s lots of room for improvement with my financial institution. What about budgets? If you pay cash for everything, you may as well stick with the envelopes. If you pay with credit card, once again, the technology is there. I just entered an expense report at work and the system has visibility into expenses charged to my corporate card. It was able to pre-populate the category of the expense by looking at who the payee was. Take this a step further, and it would be great if I could place controls over the charges (this would be very good for debit cards) so that I wouldn’t be warned (or even stopped) that I was going to blow the budget with a particular purchase. This would be great for kids, as well, where a parent could give them a limited access debit card that could only spend up to a budgeted amount and only for certain categories of expenses.

What about those long term items like vacations and saving for Christmas presents? Why on earth should I need to open up another account to do this? Can’t the bank allow me to create a “virtual” account where money can be transferred in and out, but checks and debit card transactions couldn’t go against it?

It’s certainly true that one can probably execute sound financial management with today’s tools, but it just seems to me that it can be made much easier, and if it’s easier, maybe more people will have better luck with it. So, what do you think? I’m of the opinion that someone out there has to be doing this already, it seems too obvious for someone not to be jumping all over it. If someone has, please comment or send me mail. Maybe one of the new Internet banks is doing this today. If not, well, make you thank me for the idea and give me a free toaster or something when I open my account.